The Fierce Guardian of Destiny: A Study of Gulikan Theyyam in North Malabar

I. Introduction: The Enforcer of Cosmic Balance

1.1. Gulikan Theyyam: The Paradoxical Deity of Death and Protection

Gulikan Theyyam stands as one of the most unique and intensely powerful manifestations in the rich pantheon of North Malabar’s ritual arts. Unlike many other Theyyams that focus primarily on fertility, valor, or prosperity, Gulikan embodies the quintessential paradox of life: he is the manifestation of the Hindu God of Death, Yama[1], yet he is fervently invoked for protection from evil and negative forces.[3] This deity is the enforcer of cosmic balance, destiny, and inexorable justice.[4]

The essence of Gulikan is bound up in the understanding that he does not merely deliver death; he controls the transition between life and demise, acting as a liminal figure of ultimate divine power. Devotees in districts like Kasaragod and Kannur hold this Theyyam in particularly high regard, recognizing that only the one who governs death can grant absolute protection and transcendence in the mortal world.[4] This understanding transforms the ritual from a fearful spectacle into a profound engagement with cosmic inevitability.

1.2. Why Gulikan Matters: Bridging Macro-Cosmic Forces and Local Devotion

The widespread reverence for Gulikan demonstrates a crucial socio-religious principle within the North Malabar tradition: the localization of universal, abstract concepts like death. The fear of Yama, the God of Death, is universal. However, by manifesting Yama’s agent, Gulikan, through a human performer, the community gains agency over this profound existential fear. The ritual domestication of death allows the community to confront mortality head-on.

Worshipping Gulikan is actively done to overcome the fear of death, to seek healing for serious illnesses, and to conquer seemingly insurmountable challenges.[5] The transformation experienced by the devotee witnessing the performance is a surrender of the ego. As described in sacred texts, to stand before the fierce form of Gulikan is to recognize his fury as compassion in disguise. This process transforms annihilation into a spiritual purification, showcasing Theyyam’s function as a deep psychological and social mechanism that guides the devotee to "dissolve, and to evolve".[5]

II. The Mythological Tapestry: Origin and Identity of Gulikan

2.1. The Birth from Lord Shiva's Left Toe: Restoring Order

The origin of Gulikan is rooted in high Hindu mythology, specifically the legends concerning Lord Shiva. The story recounts a time when Lord Shiva, in a divine fury, opened his third eye and reduced Yama, the original deity responsible for life’s end, to ashes. With death banished, cosmic order collapsed, and creation stood still.[5]

To restore this essential balance, Lord Shiva intervened. Gulikan was not merely appointed, but was born from the tip of Shiva’s left toe.[1] This dramatic genesis emphasizes his connection to the most primal aspect of Shaivite power. Gulikan was immediately tasked with overseeing life and death, becoming the new executor of cosmic order and destiny. He is often depicted bearing the trident (trishul), Shiva's symbol of justice, and the rope of karma, signifying his role as Shiva's trusted attendant and warrior.[4] By restoring the mechanism that ensures death is inevitable, Gulikan maintains the fundamental integrity of the cosmos.[4]

2.2. Gulikan and the Planetary Influence: The Son of Shani

Gulikan’s mythological identity extends beyond the realm of Theyyam into traditional Kerala astrology. Here, he is intimately linked with the planet Saturn (Shani), revered as the son of Lord Shani.[6] This astrological association gives rise to the concept of Gulika Kaal or Gulika Kalam, a specific period of time governed by Saturn that is considered inauspicious.[6]

The period of Gulika Kaal is generally avoided for initiating any significant or auspicious activities because of a deeply rooted belief: any task executed during this time is destined to be repeated or cycled back.[6] This is why activities such as death-related rites and rituals are strictly avoided during Gulika Kaal; the community seeks to prevent the repetition of demise.[6] This linkage between Gulikan and Shani—the cosmic force associated with consequence, fate, and time—reinforces Gulikan’s position as the executor of universal law.[5] The connection confirms that Gulikan is not merely a regional spirit, but a divine observer who manages the long-term, inescapable consequences of destiny and the cyclical nature of existence.

2.3. Maarana Gulikan: The Tantric Interpretation of Ego Dissolution

Within the spectrum of the Gulikan cult, the manifestation known as Maarana Gulikan carries a deeply philosophical and Tantric significance. Maarana is recognized in the ancient science of Tantra as one of the six powerful Shatkarmas (operations), historically associated with destructive potential.[5]

However, the understanding of Maarana Gulikan elevates this concept beyond simple destruction. Witnessing this specific Theyyam, one of the rarest manifestations, is recognized as a profound ritual of death—not of the physical body, but of the ego.[5] For the spiritual seeker (Saadhak), the sacred purpose of Maarana Gulikan is to incinerate personal illusions and pride. This divine force acts as a purifier of the inner world, offering a pathway to be reborn in silence and light, free from boundaries and fear. Maarana Gulikan, therefore, transcends the role of a guardian against external threats, becoming a potent symbol of spiritual dissolution and enlightenment.[5]

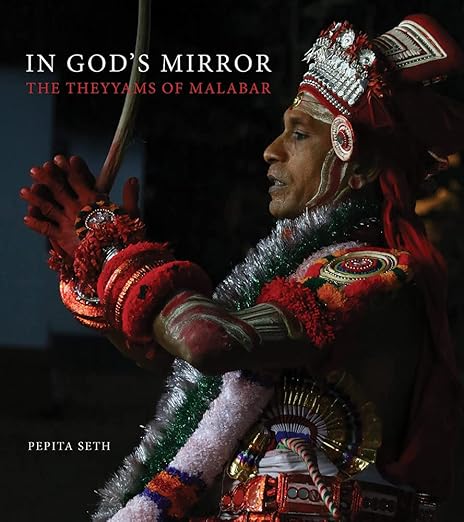

III. The Sacred Kolam: Visualizing the Destroyer of Fear

The ritual preparation of the Gulikan performer—the creation of the Kolam—is an elaborate process that transforms the human body into a vessel for the divine, relying heavily on symbolic imagery and indigenous materials from the North Malabar environment.

3.1. Mukhathezhuthu (Face Painting) and Mask

The application of Mukhathezhuthu (face painting) uses organic, natural pigments. Red is the dominant color, embodying the deity's energy, power, and fierce anger.[9] This traditional color is obtained by mixing turmeric and limestone.[9] The intricate facial and eye make-up involves detailed lines, each holding specific religious significance, contributing to the fearsome yet magnificent persona of the deity.[11]

To complete the transformation, the performer dons a typical mask. A crucial visual identifier of Gulikan Theyyam is the indelible mark of Lord Shiva’s trident (trishul) on the mask’s forehead.[1] This symbol immediately links Gulikan to his Shaivite origins and underscores his role as an agent of cosmic balance, distinguishing his visual representation from other fierce deities associated with death or war. The mask itself is often crafted from wood, such as areca palm wood, and painted with vibrant shades of red, white, yellow, and black for definition.[2]

3.2. The Majestic Mudi (Headgear): Symbolism and Construction

The most iconic element of the Gulikan Kolam is the Mudi (headgear). This huge, innovative structure is typically made from the trunk or spathe of the areca nut palm and is intricately decorated with tender leaves.[1] It is often described vividly as resembling a "huge ladder" mounted upon the performer's head.[1]

The monumental size and structure of the headgear carry profound symbolic meaning beyond mere ornamentation. Since Gulikan is born from Shiva’s foot[1]—the grounding, lowest point of the supreme deity—and is tasked with enforcing destiny, the towering Mudi visually represents the ascent from the mortal plane. The image of a ladder strongly suggests Gulikan’s function as a sacred intermediary or transition point, providing a direct pathway for devotees to transcend their earthly fears and connect directly with the immense, powerful forces of the cosmos. This physical manifestation of the Kolam powerfully reinforces the narrative of divine justice and transcendence.

3.3. Attire and Ornaments: Indigenous Materials

The remainder of the attire confirms the deep connection between the Theyyam ritual and the local ecology of North Malabar. The ornaments used to decorate the area around the clothes are a unique mixture of woven coconut leaves.[1] The waist dress is also traditionally crafted from coconut leaves or bamboo slivers.[9]

Gulikan, like other Theyyam figures, is adorned with metallic ornaments, including bangles known as Katakam and Chutakam, and small anklets.[9] The conscious use of natural, agrarian materials like areca palm, bamboo, and coconut fronds for the divine costume underscores the ritual's indigenous, tribal roots.[12] This reliance on the local environment fundamentally links the cosmic, powerful deity of death and destiny back to the land and the community that sustains the tradition.

IV. Ritual Ecology and Sacred Geography (Thanams)

4.1. The Rhythm of Performance: Time, Intensity, and the Vellattam

Gulikan Theyyam is an essential and inevitable constituent in a majority of Kaliyattams, the grand Theyyam festivals of North Malabar.[19] Performances are typically conducted late at night or very early in the morning, between 2:00 AM and 3:00 AM, which are considered the preferred hours for powerful deities to manifest.[4] The performance itself is marked by distinctive, intricate dance steps that set Gulikan apart from many other Theyyams.[19] The slow build-up of the dance, rhythm, and chanting creates a spiritual aura that is exhilarating for the audience and conducive to the performer’s divine trance.[4]

The full Mereka Theyyam performance is preceded by the Gulikan Vellattam (or Vellattu), an invocatory ritual equivalent to the Thottam (the ritual chanting of the deity’s origin story).[18] The Vellattam is a more vigorous and vibrant ritual through which the mortal human performer undergoes the necessary transformation into the divine self, preparing the vessel for the deity’s full embodiment.[18]

The sheer necessity of Gulikan’s presence in a Kaliyattam—a festival dedicated to deities of protection, sustenance, and fertility[20]—reflects a comprehensive theological view. By including the deity of death and justice, the festival acknowledges that protection from misfortune and stability in life are intrinsically linked to the absolute cosmic law Gulikan enforces. His inclusion ensures that the community placates and receives blessings from the very force that governs the end of existence, thereby guaranteeing a complete cycle of divine protection.

4.2. Significant Thanams and Kavus

The ritual spaces where Theyyam is performed are known as Thanams (sacred centers), Kavus (sacred groves), or ancestral homes, acting as critical points of spiritual power. The most famous and widely respected center for Gulikan worship is the Benkanakavu (also known as Veeranakavu) in Nileshwar, Kasaragod district.[21] This location, central to the town whose name derives from Lord Shiva (Neeleswaram, the Blue God), underscores the primary Shaivite nature of the deity.[21]

The organization of the festival at Benkanakavu is a major community undertaking, arranged biennially by adjacent high-caste families, including the Koroth Nair Tharavadu, Kazhakakkar, and Kolakkar.[22] Gulikan Theyyam is also performed annually in other important regional temples, such as the Pattare Paradevatha Kshethram near Nadapuram in Kozhikode.[22] The performance schedules show the existence of different forms of the deity, such as Karim Gulikan and Maarana Gulikan, each associated with specific ritual timings.[23]

V. Socio-Religious Dynamics: The Performers and the Community

5.1. The Carriers of the Divine: Caste and Performance

Theyyam is a revered folk tradition that enjoys veneration from people across all communities, transcending traditional caste boundaries in terms of devotion.[2] However, the ritualistic performances themselves are traditionally and principally carried out by individuals belonging to specific Scheduled Castes and tribes. The Malayan and Vannan communities are recognized as the chief traditional performers.[2] Other communities, including the Pulayan, Velan, and Mavilan, also participate in these sacred duties.[2]

The specialized roles maintained by these communities are essential for channeling the divine energy. In the ritual space of the Theyyam, where the divine power descends among the people, the performer becomes the living deity.[2]

5.2. Divine Justice and the Truth Mandate

Gulikan Theyyam serves a vital function as a mechanism for immediate justice and societal cohesion. When the performer is embodied by the deity, he enters a trance and speaks the divine will. A core belief surrounding Gulikan is the "Truth Mandate": once dressed in the Kolam, the performer is believed to be fundamentally incapable of lying.[4] His words are treated by the community as divine truth.[4]

Villagers approach Gulikan not with overwhelming fear, but with deep respect, believing that he will uphold justice, deliver divine judgment, and provide direction and moral clarity.[4] While in a trance, the deity answers questions, gives blessings, and delivers commentary on community affairs.[4] This practice facilitates the resolution of grievances and unresolved issues within the village structure, acting as a powerful instrument that influences the thoughts and practices of Malabar society.[4]

This judicial function is also underpinned by a temporary, yet powerful, ritual reversal of the social hierarchy. The performance grants individuals from historically marginalized castes (such as Malayan and Vannan) the temporary status of the supreme divine authority—an agent of Lord Shiva himself.[1] During the performance, this individual’s word holds immutable sacred weight, respected by people of all castes, including the Nambiar and Thiyya communities.[10] This mechanism acts as a critical social safety valve, allowing a channeled voice to adjudicate conflicts and provide moral guidance, ensuring social stability through the periodic intervention of sacred law.

VI. Comparative Ritual: Gulikan Theyyam versus Gulikan Thira

6.1. Defining the Ritual Forms: Conceptual Differences

While the terms Theyyam and Thira (or Thirayattam) are both used to describe ritual dances performed by men embodying deities in North Kerala, and are sometimes used interchangeably with the term Kolam, significant differences exist between them.[19]

The word Theyyam is derived from Daivam, meaning 'God.' The ritual is based on the premise that the performer becomes the living God, offering blessings directly to the people.[19] Thira, generally performed in specific shrines called Kaavukal,[22] is sometimes characterized as representing a more furious or intensely energetic form of the deity.[23] The rituals are classified differently, though both are rooted in Shaivite traditions and ancestor worship.[19]

6.2. Key Distinctions in Costume, Spectacle, and Timing

- Timing: Gulikan Theyyam generally occurs late at night or early morning.[4] Gulikan Thira is specifically noted for being performed after midnight, reinforcing the idea of it being a manifestation of the furious divine form.[23]

- Costume and Headgear: While Gulikan Theyyam features a huge headgear (Mudi) made of areca palm, sometimes described as a ladder,[1] Gulikan Thira is known for having a truly monumental, extremely long Mudi. This headdress is typically made of bamboo splicing, decorated with clothes and flowers, and can stretch over 50 feet, requiring tremendous physical effort and balance from the performer.[23]

- Mask: The initial dressing for Gulikan Thira may be simple, using coconut tree leaves, but during the ritual, a face mask—often designed to look like a devil’s face, depicting the furious aspect of Gulikan—is donned.[23]

The distinctions highlight that while both forms invoke the same deity, the Theyyam is focused on the embodiment of the divine protector and executor of justice, whereas the Thira often emphasizes the raw, terrifying power and fury of Gulikan, culminating in powerful blessings and solutions for the devotees.[23]

VII. The Protective Offering: Unpacking 'Gulikanu Kodukkal'

7.1. Etymology and Purpose: Warding off Misfortune

The practice known as Gulikanu Kodukkal (literally, 'giving to Gulikan' or 'offering to Gulikan') was a highly localized and preventative ritual common in the Malabar area, performed at the domestic level. This practice was undertaken specifically to ward off potential misfortune, diseases, or bad luck from the home and family unit.[24] The local belief held that the failure to perform Gulikanu Kodukkal would inevitably lead to misfortune in the household.[24] This reflects the community’s deep trust in Gulikan’s capacity to protect against the arbitrary forces of ill-destiny and decay.

7.2. Community Expertise and Classification

The performance of Gulikanu Kodukkal often involves specialized, indigenous expertise. Specifically, the Karimbala tribe, particularly those residing in the Kolathur village of Kozhikode district, are recognized for their mastery of this ritual.[24]

In some contexts, the ritual performance of Gulikan is referred to as Madymakarma.[24] This term implies a specialized ritual of intermediate complexity, suggesting that Gulikanu Kodukkal operates outside the large, public Kaliyattam festivals, functioning instead as a highly localized form of protective magic or ritual managed by specific indigenous communities for domestic protection. This specialization demonstrates the deep integration of Gulikan’s cult into the varied social fabric and indigenous knowledge systems of North Malabar.

7.3. Ritual Elements and Sociological Significance

While detailed, step-by-step descriptions of the materials and procedures of Gulikanu Kodukkal are often preserved only within the oral traditions of the performing communities, the ritual’s sociological role is clear: it maintains harmony by managing the boundary between safety and misfortune. The preparation and offering likely involve traditional folk foods and rituals, where elements such as the materials used for food, their mixture, method of preparation, and even the time and place of eating served as essential markers in folk life.[24]

The significance of Gulikan in this context expands his role from a celestial 'executor of destiny' to a powerful, immediate ecological and domestic guardian. Theyyam rituals are deeply influenced by the region’s ancient agrarian culture.[15] Just as the Kayattukar (attendants associated with Gulikan rituals) historically protected agricultural lands using ropes and rods from cattle[16], Gulikanu Kodukkal protects the spiritual boundaries of the home and family. Gulikan thus safeguards the Malabar community's most fundamental units—the land, the resources, and the family—from destructive forces and ill-luck, embodying an essential force of protection and stability.

VIII. Conclusion: Gulikan—A Living Tradition of Fearless Devotion

Gulikan Theyyam remains a profound cultural touchstone in North Malabar, embodying a complex convergence of Hindu cosmology, Tantric philosophy, and indigenous folk practices. He is simultaneously the fearsome agent of death born from Lord Shiva’s toe, the temporal force governing inevitable consequences through his association with Shani and Gulika Kaal, and the embodiment of spiritual liberation through the concept of Maarana Gulikan.[25]

The ritual preserves ancient artistic heritage while actively shaping community life. Through the magnificent Kolam—characterized by the mask bearing the trishul and the towering Mudi—the performer transcends humanity to become a direct conduit for divine justice.[26] This ritualized presence, conducted primarily by the Malayan and Vannan communities, provides a mechanism for conflict resolution and spiritual guidance, temporarily inverting the social order by elevating the performer's pronouncements to divine truth.[25]

Furthermore, the domestic practice of Gulikanu Kodukkal illustrates the deity’s pervasive influence, extending his protection from the cosmic sphere into the very heart of the Malabar home.[27] Gulikan Theyyam is, therefore, more than a performance; it is a sacred destruction that leads to rebirth, a fierce expression of divinity that empowers the devotee to overcome fear, and an enduring testament to the rich, living tradition of Kerala folklore.[28]

References

- J.D. Freeman (1999). Gods, Groves, and the Culture of Nature in Kerala. Routledge. Link

- S. Blackburn (1986). The Keralite Theyyam and the Hero Cult Tradition. Kerala Folklore Academy Reports. Link

- K.N. Panikkar (2002). Culture and Consciousness in Modern India. Oxford University Press. Link

- A. Sreedhara Menon (1979). Social and Cultural History of Kerala. D.C. Books.

- G. Tarabout (1988). Sacrifices et Société en Inde du Sud. CNRS Editions. Link

- K. Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai (1963). Studies in Kerala History. Kerala University Press.

- K. Ayyappapanicker (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. Link

- Kerala Folklore Academy Reports. Various Issues. Link

- Kolathiri Folklore Series (Specific studies on Gulikan Theyyam), Kerala Folklore Research Centre. Link

- Kerala Tourism (Official Website) – Theyyam Overview. Link

- Academic Journal Article: Menon, R. (2015). “Gulikan Theyyam: Ritual and Social Dynamics in North Malabar.” Journal of South Indian Folklore Studies, Vol. 12(2), pp. 45–67. Link

- Tarabout, G. (1992). “Sacred Groves and Deity Worship in Kerala.” South Asian Anthropological Journal, 5(1), pp. 22–38.