Explore Kerala's Vibrant Traditions

Kalaripayattu

One of the oldest martial art traditions in the world, blending physical discipline with spiritual training.

Learn More

Aranmula Kannadi

The legendary metal mirror of Kerala, crafted with secret alloys and unmatched precision.

Learn More

Folk Architecture

Traditional homes, temples, and ponds reflecting Kerala’s ecological harmony and cultural values.

Learn More

Beypore Uru

Magnificent wooden ships hand-crafted at Beypore, symbols of Kerala’s maritime heritage.

Learn More

Folk Medicine of Kerala

Healing traditions rooted in Ayurveda and indigenous practices using herbs and rituals.

Learn More

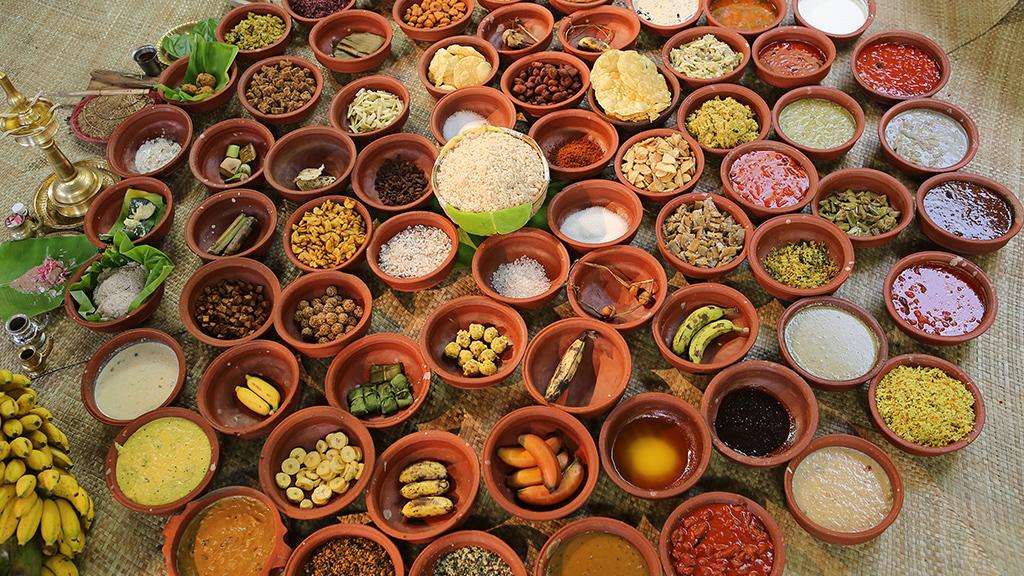

Aranmula Vallasadya

A grand ritual feast served to oarsmen, showcasing Kerala’s rich temple food culture.

Learn MoreMaterial Folklore of Kerala: A Tangible Heritage

Folklore, at its heart, is the collective memory and creative expression of a people. While often associated with stories and rituals, it also manifests in the physical world through what is known as material folklore. This encompasses the tangible objects that communities create, use, and value, serving as concrete links to their past and reflections of their present way of life.

Understanding Material Folklore

Material folklore comprises the physical items that define a group's traditional culture, including crafts, art forms, architectural styles, and culinary traditions. It extends to everyday objects like traditional holiday foods or distinct badges, and encompasses a wide array of physical manifestations. The study of material folklore delves into the design, creation, and application of these objects, exploring the profound meanings they hold for their creators and users¹.

Far from being relics of a bygone era or confined to rural settings, material folklore thrives in contemporary contexts, from bustling cities to close-knit family units and professional groups. It is a dynamic aspect of culture, embodying deeply held values, enduring customs, and characteristic ways of thinking. This continuous evolution means that modern crafts, culinary innovations, and architectural adaptations can also be considered material folklore, provided they integrate traditional elements and are informally transmitted within a social group². This broader perspective allows for a richer appreciation of how traditions persist and transform.

The significance of material folklore lies in its fundamental role in preserving cultural heritage, transmitting generational knowledge, fostering social cohesion, and inspiring ongoing creativity. These tangible expressions offer a direct window into historical periods, illuminating past beliefs and practices. Through the preservation and active practice of these material traditions, communities maintain a profound connection to their origins and distinct identity. This shared heritage also strengthens a sense of belonging among individuals, reinforcing collective identity. Objects, in this context, are not merely functional or decorative; they are imbued with stories, values, and reflections of social structures. A traditional garment, for instance, communicates identity or social standing, while a ceremonial dish carries communal memories and ritualistic importance.

Global Expressions of Material Folklore

Material folklore is a universal human phenomenon, appearing in countless forms across the globe. These tangible elements offer deep insights into diverse ways of life, shared values, and historical journeys, from the intricately woven textiles of Andean communities to the unique culinary practices of remote islands.

Material culture can be broadly categorized into movable objects—those easily transported—and immovable objects—those fixed in place. Movable examples include traditional clothing, toys, various art forms, musical instruments, distinctive cuisines, ornaments, historical weapons, coins, jewelry, and masks. Immovable examples encompass places of worship, monuments, ancient cave paintings, and traditional residential structures. Specific global instances highlight this diversity: traditional Dutch wooden clogs (klompen), Native American Dreamweavers, Chinese red lanterns used during the New Year, and the elaborate coffins of ancient Egypt. Culinary traditions, too, vary dramatically, from the rich, cream-laden dishes of French cuisine to the spicy, chili-infused meals of Thailand, often reflecting the intermingling of cultures and the availability of local ingredients.

While the specific forms of material folklore differ across cultures, their underlying purposes remain consistent: to preserve heritage, convey knowledge, build community bonds, and spark creative expression. Regional variations in folklore are shaped by local geography, historical events, and social structures. For example, narratives from Rajasthan might emphasize heroism due to the region's historical conflicts, whereas tales from Kerala often highlight nature and spirituality, reflecting its lush landscapes³. This principle extends to material culture, where local resources and historical interactions directly influence the development of specific crafts, foodways, and architectural styles.

Material culture also serves as a historical and technological record. Weapons, for instance, provide tangible evidence of a culture's technological advancements over time. Different styles of arrowheads found at archaeological sites can indicate the period of use and the specific cultural group that inhabited the area. This demonstrates that material folklore is not just about tradition but also about the evolution of human ingenuity and the adaptation of technology.

Furthermore, material and intangible cultural heritage are frequently intertwined and cannot be fully separated. A Kathakali mask, for example, is a physical object, but its full significance is understood only in relation to the performance in which it is used—a social and intangible aspect—and the stories it embodies—a verbal and intangible aspect. Thus, when exploring material folklore, it is essential to acknowledge the intangible elements that give these objects their complete meaning, enriching the understanding without delving deeply into the intangible forms themselves⁴.

Kerala's Tangible Heritage: A Synthesis of Influences

Kerala, possesses a material folklore deeply embedded in its distinctive geography, extensive history of trade, and a rich synthesis of diverse cultural influences. The state's lush landscapes, abundant natural resources, and centuries of interaction with various civilizations have collectively sculpted a tangible heritage that is both unique and profound.

The geographical position of Kerala on the southwestern Malabar Coast, bordered by the Western Ghats to the east and the Arabian Sea to the west, has historically provided a degree of isolation from mainland invasions. This unique setting allowed for the evolution of distinct social institutions and art forms. The region's historical prominence as a spice exporter, dating back to 3000 BCE, drew traders from ancient civilizations⁵ and later, European colonizers such as the Portuguese in the 15th century. This long history of global trade profoundly shaped Kerala's material culture, introducing new materials, techniques, and tastes. The culture of Kerala itself is a synthesis of Aryan and Dravidian influences, refined over centuries through interactions with various parts of India and abroad⁶.

The state's natural resources have played a fundamental role in shaping its material culture. The abundance of materials like coconut, timber, clay, and laterite stone has directly spurred the development of specialized crafts, architectural styles, and culinary practices. For instance, the widespread use of coconut in cuisine and crafts is a direct outcome of its plentiful availability. This close relationship between available resources and the development of specific material folklore highlights an ingenious resourcefulness and deep adaptation to the local environment.

Centuries of trade and migration have intricately woven Kerala's cultural fabric. The presence of various dynasties, early Arab traders, and later European powers—including the Portuguese and British—significantly impacted its arts, architecture, and particularly its cuisine. The harmonious coexistence of Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam is visibly reflected in the diverse material heritage, including festivals, culinary traditions, and art forms. For example, the Moplah (Mapilla) Muslim community and the St. Thomas (Mar Thoma) Christians have introduced unique dishes and culinary styles, adding distinct layers to Kerala's gastronomic landscape⁷. This demonstrates how Kerala's material folklore is not a singular, purely indigenous entity, but rather a dynamic blend—a living archive of its interactions with the wider world. It is a tangible record of cultural fusion and continuous adaptation.

Crafting Identity: Traditional Arts and Handicrafts of Kerala

Kerala's artisans have, for centuries, transformed natural resources into objects of both utility and profound beauty. Each piece carries the essence of the region's cultural identity, serving as an expression of skill, devotion, and communal narratives.

Among the most iconic and unique crafts is the Aranmula Kannadi, a distinctive metal mirror crafted in Aranmula. It is renowned for its special bronze alloy and intricate design, considered a collector's item and a marvel of traditional craftsmanship⁸. The Beypore Uru, handcrafted wooden ships from Beypore, symbolizes Kerala's historical maritime trade and shipbuilding prowess⁹. The Thalankara Thoppi, a traditional cap from Kasaragod, represents a unique regional identity¹⁰.

Kerala's craft forms are diverse, utilizing a range of local materials:

- Pottery items are skillfully molded from clay into terracotta masks, jars, vases, and urns, often imbuing spaces with a rustic aesthetic.

- Lacquerware, particularly prominent in Ernakulum, involves wooden art pieces coated with lacquer and often adorned with precious metals.

- Woodcraft showcases artisans' intricate skills, with carved pieces ranging from beautiful souvenirs to miniature houseboats. Timber, abundantly available in various types, serves as a primary structural material.

- Coconut-derived products exemplify resourcefulness, transforming coconut shells and coir (fiber from husks) into eco-friendly items like vases, toys, bowls, rugs, mats, and bags.

- Screw pine products, an art form dating back eight hundred years, involve weaving the leaves of the screw pine plant into durable and naturally beautiful items such as bags, mats, and wall hangings.

- Banana fibre handicrafts utilize fibers extracted from banana plant trunks to create sustainable and eco-friendly products like bags, mats, and wall hangings.

- Bell metal crafts include utensils, lamps, and decorative items forged from bell metal, prized for their durability and resonant sound.

Textile traditions also form a significant part of Kerala's material heritage. The Kasavu Saree, an off-white cotton saree with intricate gold zari borders, is an iconic symbol of Kerala, traditionally worn by women on special occasions and festivals to signify elegance and cultural importance¹¹. Other notable handloom sarees include Balampuram and Kuthampully sarees, recognized for their zari borders and smooth textures. The Nettur Petti is an exquisite art form involving colorful and intricate artwork created with lac (resin) on wood, often depicting mythological scenes, floral designs, and geometric patterns¹².

Many material items directly represent Kerala's vibrant performing arts. Kathakali masks, colorful papier-mâché creations, depict characters from the classical dance-drama. These are highly sought-after collector's items and serve as a fascinating representation of Kerala's performing arts, mirroring the elaborate makeup and costumes used in the dances¹³. Similarly, Theyyam costumes and masks are central to this ritualistic art form, donned by performers to create an otherworldly aura as they embody deities and ancestral spirits¹⁴. Padayani masks, crafted from wood, bamboo, or clay and adorned with bright colors and intricate designs, are integral to this traditional folk art¹⁵.

The traditional crafts of Kerala are not merely static museum pieces; they represent a continuous, evolving practice. Government initiatives actively encourage and support local artisans, even educating them in new techniques to enhance their art¹⁶. This ongoing preservation and practice of material traditions ensure that communities maintain a vital connection to their heritage. This emphasis on continuity and adaptation highlights how these crafts remain relevant and are actively supported in contemporary society, rather than being confined to the past.

A compelling aspect of Kerala's material culture is its ability to bridge the sacred and the secular. Many crafts, such as Kathakali masks, Theyyam costumes, and the Nettur Petti, are deeply rooted in mythological themes, religious rituals, or traditional performing arts. Yet, these items are also widely available as souvenirs or decorative pieces. This duality reveals a fascinating transition where objects with profound sacred or ritualistic origins find new life in commercial or decorative contexts. This process, while sometimes prompting discussions about authenticity, also plays a crucial role in ensuring their survival and broader appreciation.

A Taste of Tradition: Kerala's Culinary Heritage

Kerala's cuisine is a significant component of its material folklore, offering a delicious narrative of its history, geography, and cultural diversity. It represents a culinary journey shaped by indigenous ingredients, ancient trade routes, and the unique dietary practices of its various communities.

Traditional meals hold deep cultural significance in Kerala. The Sadya, a grand vegetarian feast served on a plantain leaf, is typically reserved for ceremonial occasions such such as weddings, Onam, and Vishu. It embodies the essence of hospitality and the richness of Kerala's food culture. A full Sadya can feature approximately 20 different accompaniments and desserts. In Kerala, food transcends mere sustenance; it is a celebration of diversity and a way of life, with each dish conveying a story of the region's history and enduring traditions.

The cuisine relies on several staple ingredients and features a variety of unique dishes:

- Staples: Coconut is an omnipresent ingredient, used grated or as milk for thickening and flavoring in most dishes. Rice and tapioca form the primary starch components.

- Spices: Known as the "Land of Spices," Kerala frequently incorporates black pepper, cardamom, clove, ginger, and cinnamon into its dishes.

- Seafood: Given its extensive coastline and numerous rivers, seafood is a common and vital part of meals.

- Breakfast Items: Popular choices include Appam (a bowl-shaped pancake), Dosa (a savory crepe), Pathiri (a thin rice flour flatbread particularly favored by Malabar Muslims), Puttu, Idiyappam, Vattayappam (an oil-free snack), and Kalathappam (a fermented rice pancake).

- Specific Delicacies: Notable regional specialties include Thalassery Biryani, which uses kaima rice and a dum preparation method, originating from Thalassery¹⁷; Kozhikode Halwa; and Ramassery Idli.

The historical influences on Kerala's food culture are profound. The Portuguese, arriving in the 15th century, introduced pivotal ingredients such as potatoes, chilies, tomatoes, cashew nuts, guava, papaya, pineapple, and citrus fruits like mosambi. Their introduction of vinegar significantly influenced cooking methods. They also brought yeast, leading to the creation of leavened bread, and the concept of firewood ovens (borma). Dishes like Vindaloo, a derivative of Portuguese pork preserve, exemplify this culinary fusion¹⁸.

The Chinese influence is evident in utensils like the Chinese wok (cheenachati) and urns that were later repurposed for pickling foods. The Portuguese are also credited with introducing steaming as a cooking technique, possibly influenced by Chinese culinary practices¹⁹. Additionally, Kerala Christian cuisine showcases a blend of Middle Eastern, Syrian, Jewish, and Western styles, featuring unique dishes such as fish moli, duck roast, and mustad. Mappila cuisine, with dishes like Kuzhi Mandi, reflects a clear Yemeni influence. This rich historical layering reveals culinary folklore as a microcosm of cultural exchange. The detailed accounts of Portuguese and Chinese influences on Kerala cuisine demonstrate that it was not merely an adoption of new ingredients. Instead, new elements like vinegar, yeast, and the wok were creatively adapted to local traditions and ingredients, particularly coconut, resulting in "novel textures, flavors, and tastes". This dynamic process illustrates how Kerala's food is a living historical document of global trade and cultural interaction, absorbing and transforming external influences to create something uniquely Keralite²⁰.

Beyond its flavors, food in Kerala serves as a powerful marker of religious identity and a tool for social cohesion. The significant introduction of Muslim and Christian communities has led to unique dishes and styles within Kerala cuisine. Distinct culinary traditions are maintained by different communities, such as the specific dishes of Mappilas and Christians, and the dietary restrictions observed by some Hindus who avoid beef or pork. Simultaneously, shared feasts like the Sadya bring people together in communal celebration. This highlights how material folklore, in the form of food, reinforces social structures and strengthens community bonds.

Draped in Heritage: Traditional Dress and Adornments

The traditional attire of Kerala is more than mere clothing; it is a profound reflection of the region's climate, intricate social history, and evolving cultural norms. From simple loincloths to elegant saris, dress codes have historically conveyed status, identity, and the adaptation to external influences.

At the core of Kerala's traditional dress is the Mundu, a loincloth historically worn wrapped around the waist by both men and women, irrespective of gender, caste, or religion. For women, the traditional clothing is the Mundum Neriyatum, comprising two pieces: the lower garment (mundu) and the upper garment (neriyatu). This attire is considered the oldest surviving form of the ancient sari, typically white or cream with a distinctive colored or gold (kara) border. Over time, the Mundum Neriyatum has evolved into what is now widely recognized and celebrated as the Kerala Saree²¹.

The evolution of dress codes in Kerala provides a compelling narrative of social change and power dynamics. Until the mid-20th century, minimal clothing was common due to the humid climate, with both men and women often going bare-chested or bare-breasted. The Melmundu, or upper cloth/shawl, was used by upper castes such as Namboothiris, Nairs, and Kshatriyas, draped over the shoulder as a mark of superiority. The Melmundu Samaram (Upper Cloth Revolt of 1859) was a pivotal historical event that challenged these rigid caste-based dress codes, eventually allowing lower caste individuals to wear an upper cloth²². This struggle vividly illustrates how dress was deeply intertwined with social hierarchy and movements for reform.

The arrival of the British significantly impacted clothing styles, introducing linen and promoting "modest" dressing, which led to women adopting blouses in the early 20th century. Syrian Christians developed their unique white traditional dress, the "Chatta Mundu" (a jacket and long white garment), with specific styles like the Jubba or Kurta for men. Muslim dress features Mundu styles with wide and colored borders, distinct from Hindu and Christian variations. The influence of Gulf countries also led to the adoption of the 'Purdah' or Jilbab, and later the more modern Arabic Abaya²³.

This rich diversity in attire demonstrates that material folklore can both unite and distinguish communities within a diverse society. While the Mundu serves as a common garment across religious lines, the distinct styles adopted by Syrian Christians and Muslims highlight how different religious communities, while coexisting, maintained unique material expressions of their identity. This reflects the complex interplay of shared regional identity and distinct religious heritage.

Built to Endure: Vernacular Architecture of Kerala

Kerala's traditional architecture stands as a testament to ingenious design, meticulously harmonized with the tropical climate and abundant natural resources. These vernacular styles, passed down through generations, embody a profound understanding of local materials and environmental adaptation.

Key characteristics of Kerala's traditional architecture include distinctive sloping roofs, central courtyards known as Nadumuttam, extensive use of timber, and inviting verandahs. These elements are purposefully designed to align with the region's tropical climate, ensuring natural ventilation, providing robust protection from heavy monsoon rains, and fostering a seamless connection with the natural environment. Gable windows further enhance natural airflow and prevent overheating. This emphasis on climate-responsive design underscores how Kerala's vernacular architecture embodies deep ecological wisdom and sustainable practices, offering valuable lessons for contemporary design.

The architectural style is rooted in the Indian Vedic architectural tradition and forms a part of Dravidian architecture, with Kerala developing its own specific architectural manuals like Tantra Samucchayam and Manushyalaya-Chandrika²⁴. A unique indigenous development is Thachu Shastra, "the science of carpentry," which posits that timber, derived from living forms, possesses its "own life" when used in construction. This life must be harmonized with its surroundings and the inhabitants. This philosophical underpinning suggests that for the practitioners, material folklore is not inert; it implies a deeper, almost spiritual, connection to the built environment, making the architecture a partner in existence.

Local materials are extensively utilized in construction: laterite stone, which is abundant and strengthens upon exposure to air; timber, from bamboo to teak, serving as the primary structural material; clay, used for walls, floors, bricks, and tiles; and palm leaves, rice straw, and bamboos for thatch roofs and partition walls. The skill of Taccans (carpenters) is evident in their traditional wooden joinery techniques, often employed without the use of nails.

Architectural styles in Kerala can be broadly categorized into religious architecture, primarily encompassing Hindu temples, and some churches and mosques, and domestic architecture, which includes residential houses, palaces, and mansions. The belief system of Vastu plays a significant role, holding that every structure possesses its own life, soul, and personality, shaped by its surroundings.

The Enduring Legacy of Kerala's Material Folklore

Kerala's material folklore represents a rich and diverse collection of tangible expressions that narrate the story of a land shaped by its environment, history, and the remarkable ingenuity of its people. From intricate crafts and distinctive culinary traditions to unique dress styles and climate-responsive architecture, these elements offer a profound glimpse into the soul of Kerala.

A remarkable aspect of Kerala's material folklore is its capacity for cultural resilience and adaptation. Across all its forms—crafts, food, dress, and architecture—there is a consistent theme of continuity and transformation despite external influences such as trade, colonization, and modern advancements. Traditional attire, for instance, has evolved while retaining core elements, and cuisine has absorbed foreign ingredients, integrating them into uniquely Keralite flavors. Crafts continue to be supported by contemporary initiatives, ensuring their survival. This demonstrates how tangible traditions can adapt to new circumstances, integrate foreign elements, and even overcome social barriers, as seen in historical dress code reforms, thereby ensuring their continued relevance.

Furthermore, Kerala's material folklore beautifully illustrates the interplay of utility, aesthetics, and symbolism. Objects are not merely created for practical use, such as houses for shelter or food for sustenance, nor solely for their visual appeal. They are deeply imbued with symbolic meanings. Kathakali masks, traditional garments, ceremonial meals, and even the philosophical underpinnings of its architecture all carry significant cultural weight beyond their immediate function. This multi-layered nature means that material folklore serves practical needs, delights the senses, and, most importantly, reinforces cultural values, historical narratives, and social structures.

Preserving and understanding this material heritage is paramount. It provides a tangible link to the past, strengthens cultural identity, and continues to inspire future generations, ensuring that the unique spirit of Kerala endures.

References

The following are sources cited or referenced in the article, "Material Folklore of Kerala: A Tangible Heritage."

- ¹ Glassie, H. The Spirit of Folk Art: The Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe. Abrams, 1989.

- ² Bronner, Simon J. "American Material Culture and Folklife: A Prologue and a Problem." Western Folklore, vol. 50, no. 1, 1991, pp. 27-41.

- ³ Ramanujan, A.K. "Is There an Indian Way of Thinking? An Informal Essay." India through Hindu Categories. Edited by McKim Marriott, Sage Publications, 1989.

- ⁴ UNESCO. "Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage," 2003.

- ⁵ Pannikar, K.N. "The Malabar Coast and its Spice Trade." Journal of Indian History, vol. 63, no. 1, 1985.

- ⁶ Sreedhara Menon, A. A Survey of Kerala History. Sahitya Pravarthaka Co-operative Society, 1994.

- ⁷ George, Lathika. The Suriani Kitchen. Hippocrene Books, 2017.

- ⁸ Subramanian, S. "Aranmula Metal Mirror: The Craft and the Tradition." Indian Journal of Traditional Arts, vol. 15, 2012.

- ⁹ National Geographic. "The Beypore Uru: A Lasting Tradition." National Geographic, 2015.

- ¹⁰ Namboodiri, A. "The Thalankara Thoppi: A Symbol of Malabar Identity." Kasaragod Heritage Society Journal, 2008.

- ¹¹ Nambiar, G. A. Handloom Weaving in Kerala. Kerala Handloom Board, 2005.

- ¹² Nampoothiri, P. G. "The Art of Nettur Petti." Kerala Crafts Council Journal, 2011.

- ¹³ Zarrilli, Phillip B. Kathakali: A Guide to the Production. Routledge, 2000.

- ¹⁴ Nambiar, A.K. "Theyyam: The Ritual Art of North Malabar." Journal of Folklore Research, 2007.

- ¹⁵ Narayanan, K.C. Padayani: The Masked Ritual Dance of Kerala. Kerala Folklore Academy, 2013.

- ¹⁶ Department of Industries and Commerce, Government of Kerala. Report on Handloom and Handicrafts Sector. Government of Kerala, 2022.

- ¹⁷ Pillai, S. The Culinary History of Kerala. Kerala University Press, 2018.

- ¹⁸ Sreemol, C. E. T. "Colonial Influences on Kerala Cuisine." The Food History Journal, vol. 12, 2015.

- ¹⁹ Narayanan, T. V. "Foreign Influence on Kerala's Food Culture." The Indian Food Review, 2010.

- ²⁰ Achaya, K. T. Indian Food: A Historical Companion. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- ²¹ Anupama, B. "A Historical Study on the Evolution of Traditional Costumes of Kerala." International Journal of Fashion Technology, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020.

- ²² Jeffrey, Robin. The Decline of Nayar Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore, 1847-1908. Manohar, 2018.

- ²³ George, K.M. A History of Kerala. University of Kerala, 2011.

- ²⁴ Kramrisch, Stella. The Hindu Temple. vol. 1, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1946.