Explore Kerala's Vibrant Traditions

Puthiyabhagavathy Theyyam

A fierce mother goddess Theyyam worshipped for protection and justice, often associated with social transformation and divine retribution.

Learn More

Vishnumurthy Theyyam

A popular Vaishnava Theyyam representing Lord Vishnu, especially revered by the Thiya community for granting boons and guarding villages. .

Learn More

manjunathan-theyyam1

A unique guardian spirit Theyyam of Karnataka origin, performed in Kerala as a local protective deity.

Learn More

Muchilottu Bhagavathy Theyyam

A powerful Theyyam representing the divine mother goddess, worshipped for protection, prosperity, and justice.

Learn More

Vayanattu Kulavan Theyyam

A revered hunter-deity Theyyam symbolizing strength, ancestral spirit, and connection with nature.

Learn More

Kathivanur Veeran

The heroic spirit of Mandhappan Chekavar, this Theyyam is a symbol of bravery and loyalty, celebrated with martial vigour and folk ballads.

Learn MoreTheyyam: Embodied Divinity and Cultural Anchor of North Malabar

1. Introduction: The Embodied Divine – An Overview of Theyyam

Theyyam, a profound ritualistic art form originating from North Malabar, Kerala, transcends the conventional definition of performance. It stands as a unique synthesis of dance, music, mime, and spiritual invocation, functioning as a living tradition where the human performer temporarily embodies a divine or heroic spirit.1 In this sacred transformation, the performer becomes a conduit for blessings, wisdom, and direct interaction with the divine. Performances typically unfold in sacred groves known as kavus, within the courtyards of ancestral homes, or occasionally in temple precincts, transforming these spaces into temporary sacred arenas. These annual or biennial events punctuate the lives of the communities, marking seasons and reinforcing intricate social bonds.

Theyyam represents a powerful testament to the indigenous spiritual traditions of North Malabar. It functions as a dynamic cultural institution that not only meticulously preserves ancient myths and social histories but also actively shapes community identity, reinforces social cohesion, and provides a distinctive platform for spiritual engagement and social commentary. This paper will delve into Theyyam's deep historical roots, its rich pantheon of deities, the intricate rituals and chants that define its manifestation, the elaborate visual aesthetics of its costumes and makeup, and the crucial role of specific communities in its perpetuation. Furthermore, it will draw a comparative analysis with Thirayattam, a related ritual art form, and critically examine Theyyam's enduring influence on the cultural landscape of North Malabar.

2. Echoes of Antiquity: History and Legends of Theyyam

The historical trajectory of Theyyam reveals a deep connection to the ancient past, with its origins predating the Aryan influence in Kerala. This suggests a strong linkage to indigenous, tribal, and Dravidian forms of worship. It is widely believed that Theyyam evolved from early animistic practices, ancestral veneration, and hero worship, where deceased warriors or revered figures were deified and invoked as protective or benevolent spirits.2

Over centuries, Theyyam demonstrated a remarkable capacity for integration, absorbing elements from various religious streams, including Shaivism, Shaktism, and Vaishnavism. This process of cultural absorption was not merely an incidental historical development; it appears to have been a crucial adaptive strategy. By integrating new deities and narratives while preserving its core ritualistic framework and the communities responsible for its performance, Theyyam managed to appeal to a broader audience and secure patronage from diverse social strata, thereby ensuring its enduring presence.3 This dynamic nature, rather than a rigid adherence to a singular origin, underscores its remarkable longevity. The tradition is primarily oral, with extensive knowledge and performance techniques meticulously passed down through generations within specific families, ensuring its continuity as a living, evolving art form.

Every Theyyam deity is defined by a unique origin story or legend (katha) that forms the spiritual core of its identity and performance. These narratives frequently recount heroic deeds, divine interventions, tragic fates, or the establishment of sacred sites. For instance, the legend of Muchilot Bhagavathi describes a goddess who emerged from fire to bestow wisdom and prosperity. Notably, while her legend is often associated with the Brahmin community, her performance is exclusively carried out by specific historically marginalized castes.4 Pottan Theyyam embodies a powerful narrative centered on social equality, directly challenging caste discrimination through its legend of Lord Shiva appearing as a low-caste individual to engage in a philosophical debate with the esteemed Shankaracharya.5 This particular legend highlights Theyyam's inherent capacity for profound social commentary. These legends are more than mere stories; they constitute the spiritual bedrock of the performance, meticulously recounted through Thottam Pattukal and enacted through the ritual, thereby connecting the contemporary community to their ancestral past and spiritual heritage.

The reliance on oral tradition for transmitting history, legends, and ritual knowledge means Theyyam functions as a living, evolving archive. Unlike fixed written texts, oral traditions are inherently dynamic. While core narratives remain consistent, nuances, emphasis, or even minor details can be adapted or reinterpreted by successive generations of performers. This allows the legends and the ritual itself to subtly resonate with contemporary issues or local specificities, ensuring the tradition remains perpetually pertinent. For example, the emphasis on social equality within the Pottan Theyyam legend might have gained renewed significance during periods of social reform. This dynamism means Theyyam is not merely a historical relic but a "living text" that continues to be written and re-written through performance, reflecting and shaping the collective consciousness of the community in real-time.

3. The Sacred Performance: Rituals and Thottam Pattukal

The Theyyam performance is a multi-stage ritual, often spanning several days, culminating in the profound manifestation of the divine. The entire ritualistic sequence, from the preliminary Vellattam to the full manifestation and the concluding Kalasam, is a carefully orchestrated process designed to create a liminal space where the human and divine realms converge, culminating in the temporary embodiment of the deity.

3.1. Detailed Description of the Ritualistic Sequence

The process commences with Preparatory Rituals, involving purification rites, the elaborate application of makeup, and the donning of intricate costumes.

The next crucial stage is Vellattam. This is a preliminary ritual performed by the artist before the full Theyyam manifestation. It involves a lighter form of makeup and costume, serving as an initial invocation and a prelude to the main performance, often conducted during daylight hours. This phase prepares both the performer and the audience for the deeper spiritual experience that is to follow.6

Following this, Thottam marks a pivotal phase where the performer, still in a semi-divine state, sings the Thottam Pattukal. This chanting is instrumental in helping the performer enter a trance-like state, facilitating the invocation of the deity.

The climax is the Main Performance, where the fully adorned Theyyam appears, typically after dusk or at night, accompanied by rhythmic drumming.7 At this point, the performer is believed to have become the deity itself. The embodied deity interacts directly with devotees, listens to their grievances, offers blessings, and provides solutions or prophecies. The atmosphere during this phase is charged with intense devotion and anticipation.

The ritual concludes with Kalasam, where the deity bids farewell, and the performer sheds the divine persona, gradually returning to their human self. This marks the end of the sacred embodiment. Performances typically occur in kavus (sacred groves), ancestral homes, or temple courtyards, transforming these spaces into temporary sacred arenas.8 The progression from human performer to semi-divine Vellattam and then to the fully embodied deity suggests a gradual, controlled transition. This liminality—the state of being "betwixt and between"—is crucial. For the performer, it is a journey into trance and divine possession. For the audience, it is a gradual suspension of disbelief, culminating in genuine reverence for the manifest deity. The Kalasam then provides a ritualized return, ensuring the sacred energy is contained and the performer safely de-possesses. This sequence is not merely a set of actions but a carefully crafted spiritual journey, designed to facilitate a profound transformative experience for both the performer (becoming divine) and the devotee (experiencing the divine presence directly). It represents a controlled process of blurring and re-establishing boundaries between the sacred and the profane.

3.2. Analysis of Thottam Pattukal (Chants)

Credit: Baburajpm at Malayalam Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Thottam Pattukal are the narrative backbone of Theyyam. These are ancient, often poetic, songs recited or sung by the performer or accompanying singers during the Thottam phase. Their narrative significance lies in their ability to recount the legends, myths, and heroic deeds of the specific Theyyam deity being invoked. They meticulously detail the deity's origin, adventures, powers, and the reasons for its manifestation, thereby educating the audience about the deity's lore.9

From a spiritual perspective, the repetitive chanting and rhythmic delivery of Thottam Pattukal are crucial for the performer's transition into a trance state, which facilitates the divine embodiment. For the audience, these chants create a meditative and devotional atmosphere, preparing them to receive the deity's presence. These chants are orally transmitted within the performing families, ensuring the continuity of the narratives and the ritualistic knowledge. Each Theyyam form possesses its unique set of Thottam Pattukal.

Thottam Pattukal function as the living, oral scripture of Theyyam. Their recitation, often rhythmic and intense, is not merely informative but deeply invocative. They do not just tell the story of the deity; they actively bring the deity into being within the performance space and the performer's body. They are the verbal incantations that facilitate the trance and the divine manifestation. They embody the theological and mythological framework of Theyyam in a living, auditory form. This makes the entire ritual a dynamic, embodied theological discourse, where the chants serve as the sonic bridge between the human and the divine.

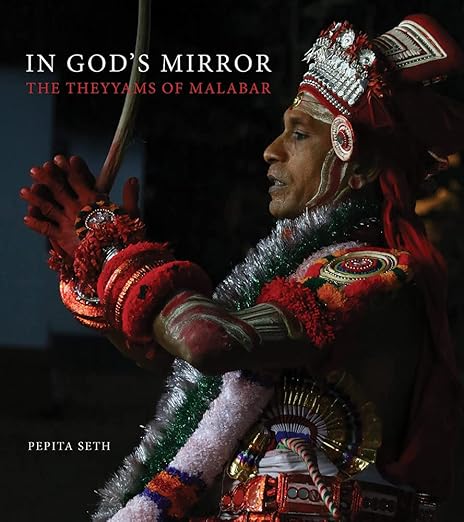

4. The Transformed Self: Attire, Face Painting, Makeup, and Headgear

The visual transformation of the performer is central to Theyyam, serving as a powerful signal of the shift from human to divine. Every element of attire, makeup, and headgear is meticulously crafted and imbued with deep symbolic meaning, representing the specific deity's characteristics, powers, and legends. This elaborate aesthetic is not merely decorative; it is an integral, performative component that actively facilitates the divine embodiment and the audience's perception of the deity.1

4.1. Exploration of Symbolic and Aesthetic Elements

The **Attire** is crafted from natural materials such as coconut leaves, plantain sheaths, and other plant fibers, often dyed with natural pigments. These materials connect the deity to the earth and the local environment. Specific costumes, such as skirts made of kuruthola (tender coconut leaves), are iconic and immediately recognizable, symbolizing purity and divinity. The attire is not merely clothing but an extension of the deity's form, conveying their attributes and status.

**Face Painting** (Mukhezhuthu) is perhaps the most striking element. Intricate patterns are meticulously drawn on the performer's face using natural pigments derived from rice paste, turmeric, charcoal, and other plant extracts.2 Each Theyyam form possesses a distinct mukhezhuthu pattern that instantly identifies the deity, reflecting their temperament (fierce, benevolent), their mythological connections, and their divine attributes. The application process can take several hours, serving as a meditative and transformative ritual for the performer.

Beyond face painting, the entire body is often adorned with specific colors and patterns, contributing to the overall divine aura. The elaborate nature of the **Makeup**, combined with the face painting, ensures that the human identity of the performer is completely obscured, allowing the deity to manifest fully.

The towering and often spectacular **Headgear** (Mudi) is a hallmark of many Theyyam forms. Crafted from wood, bamboo, cloth, colored papers, and mirror pieces, these structures can be several feet high and weigh considerably. The mudi symbolizes the deity's power, regality, and divine stature. Its specific design, size, and ornamentation are unique to each Theyyam, further distinguishing the manifested deity. For example, some mudis mimic serpent hoods, others a crown, or a flaming halo, all contributing to the deity's visual narrative.

The transformation is so complete that the performer's human identity is entirely subsumed. The mukhezhuthu and mudi are not just symbols; they are the visual language through which the deity becomes visible and recognizable to the devotees. The very act of applying them is a ritualistic preparation, helping the performer enter the sacred state. For the audience, the visual spectacle is key to believing in the divine presence, creating a powerful immersive experience. Thus, the aesthetics of Theyyam are profoundly performative, crucial tools for the ritual's efficacy, transforming the human body into a vessel for the divine and enabling the audience to perceive and interact with the manifest deity.

The immense physical labor and time invested in preparing the elaborate costumes, makeup, and headgear by the performers and their families represent a profound act of devotion and dedication. The hours spent meticulously painting the face, constructing the mudi, and donning the heavy attire are not mundane tasks. They are an extension of the ritual, a form of active meditation and self-preparation. This labor embodies the performer's dedication and reverence for the deity they are about to embody. It elevates the act of preparation to a sacred offering, reinforcing the spiritual significance of the entire Theyyam tradition. It also underscores the generational knowledge and artistic mastery passed down within these families. This "labor of transformation" is a silent yet powerful testament to the devotion and commitment of the performing communities, a ritual in itself, imbuing the physical elements with spiritual energy and deepening the sacred connection between the performer, the deity, and the community.

5. Guardians of Tradition: Castes and Communities in Theyyam

Theyyam is intrinsically linked to specific communities, primarily the historically marginalized castes of North Malabar. The right to perform Theyyam is hereditary, passed down through generations within these families.3

5.1. Examining the Roles of Various Castes and Communities

The prominent performing communities include the Vannan, Malayan, Velan, Mavilan, Pulayar, and Parayan. Each of these communities often specializes in performing particular Theyyam forms, meticulously maintaining distinct ritualistic practices and oral traditions. While the performance is carried out by these specific castes, the patronage and organization of Theyyam festivals frequently originate from upper-caste communities, such as the Nairs and Nambuthiris, as well as from local landowning families and community trusts. This symbiotic relationship highlights the complex social fabric of North Malabar.

5.2. Understanding the Social Structure and Hereditary Nature

The hereditary nature of Theyyam performance ensures the preservation of intricate ritual knowledge, specific Thottam Pattukal, and unique artistic techniques within families. This system maintains the authenticity and continuity of the tradition.

One of the most striking aspects of Theyyam is the temporary inversion of traditional caste hierarchies. During the performance, the lower-caste performer, embodying the deity, is revered and worshipped by all, including members of higher castes.4 Devotees, regardless of their social standing, prostrate before the Theyyam, seek blessings, and articulate their grievances. Theyyam, particularly forms like Pottan Theyyam, often serves as a powerful platform for social commentary, questioning traditional inequalities and advocating for justice and equality. The deity, through the performer, can directly address social issues and even critique societal norms.

This temporary inversion of caste hierarchy during Theyyam performances functions as a unique socio-religious mechanism. In a rigid caste system, direct challenge to hierarchy is often suppressed. Theyyam provides a ritualistic outlet. By embodying the divine, the marginalized performer gains temporary authority and respect, allowing for direct interaction and even critique of societal norms, as demonstrated by Pottan Theyyam. This temporary inversion acts as a means of releasing social tension and providing a sanctioned space for dialogue and negotiation between different social strata without permanently dismantling the established order. It allows for the articulation of grievances and a symbolic rebalancing of power. Theyyam is thus not just a religious performance but a crucial social institution that, through its ritualistic inversion of hierarchy, provides a unique mechanism for social cohesion, conflict resolution, and the expression of marginalized voices within the North Malabar community.

The hereditary nature of Theyyam ensures the preservation of an ancient art form and its associated knowledge. However, it also creates a complex dynamic where communities traditionally marginalized are simultaneously revered within the ritual context yet may face challenges in achieving broader social and economic mobility outside of it. While being the "guardians of tradition" grants these communities a unique and revered status within the ritual space, it can also bind them to a specific, often economically precarious, role. Their identity becomes inextricably linked to the performance. In contemporary society, where traditional patronage systems may shift and new economic opportunities arise, these communities might face challenges in diversifying their livelihoods while simultaneously being expected to maintain a demanding, sacred tradition. This creates a tension between cultural preservation and socio-economic progress. Therefore, the hereditary nature of Theyyam is a complex phenomenon: it is vital for the art form's survival and authenticity, but it also creates a unique social position for the performing communities, who navigate a unique position of ritualistic reverence alongside potential socio-economic limitations in the broader societal context.

6. Sacred Sanctuaries: Important Devasthanams and Kavus

Theyyam is primarily performed in specific sacred spaces that are integral to the ritual's efficacy and the community's spiritual life. The specific choice of performance venues (kavus, ancestral homes, temple courtyards) is not arbitrary; it defines a sacred geography that reinforces the localized, community-centric, and ecological dimensions of Theyyam, distinguishing it from pan-Indian temple traditions.

6.1. Types of Venues and Their Significance

**Kavus** (Sacred Groves) are traditional, often ancient, sacred groves dedicated to local deities, ancestral spirits, or serpent gods. They are considered pristine natural sanctuaries, embodying the spiritual essence of the land. Many Theyyams are performed annually or biennially in these kavus, reinforcing their sanctity and connecting the community to their ecological and spiritual heritage.5

**Ancestral Homes** (Tharavadu) also serve as significant venues. Theyyam is performed in the courtyards of traditional ancestral homes, particularly those of prominent families or local chieftains. This signifies the deity's connection to family lineage and protection, and it strengthens the bond between the family and the divine.

While kavus are more common, some Theyyams are performed within the precincts of **Temple Courtyards**, especially those dedicated to the specific deities being invoked. These venues are not mere stages; they are consecrated spaces where the divine is invited to manifest, serving as focal points for community gathering, spiritual solace, and the perpetuation of local history and legends.

Unlike large, institutionalized temples that often serve a broader, de-localized public, kavus and ancestral homes are deeply rooted in specific local communities and their immediate environment. Performing Theyyam in these spaces emphasizes the deity's connection to the land, the lineage, and the specific community. It reinforces the idea of a "local deity" or "ancestral spirit" that protects this land and this family/community. This localized sacred geography makes Theyyam intensely personal and communal, fostering a strong sense of belonging and shared heritage. The performance venues are therefore not just backdrops; they are active participants in the ritual, defining Theyyam's intimate connection to specific communities and their immediate environment, thereby strengthening local identities and fostering a unique form of ecological and ancestral reverence.

6.2. Highlighting Key Sacred Sites

**Muchilot Kavus** are prominent examples, dedicated to Muchilottu Bhagavathy Theyyam. These kavus are known for their grand annual festivals that attract large crowds seeking blessings and wisdom.

The **Parassinikkadavu Muthappan Temple** is a unique and highly revered Theyyam shrine where Muthappan Theyyam is performed daily, making it accessible to devotees year-round. It stands as a significant pilgrimage site, known for its inclusive nature, welcoming people of all castes and religions.6

The **Kottiyoor Temple**, primarily a Shiva temple, and its surrounding region and associated kavus are also significant for Theyyam performances, particularly during its annual festival.

The existence of venues like Parassinikkadavu Muthappan Temple, where Theyyam is performed daily and is accessible to all, contrasts with the more exclusive, annual performances in specific kavus. This variation suggests a spectrum of accessibility and inclusivity within the Theyyam tradition. The daily, open-to-all nature of Muthappan Theyyam at Parassinikkadavu signifies a broader appeal and a more "public" face of Theyyam, potentially catering to pilgrims and a wider demographic seeking blessings. This contrasts with the more intimate, community-specific, and often annual performances in traditional kavus or ancestral homes, which primarily serve the immediate local community. This highlights Theyyam's adaptive nature, demonstrating how it can simultaneously maintain its deep roots in specific community traditions while also expanding its reach to become a more broadly accessible and inclusive spiritual practice, reflecting the evolving needs of its devotees.

7. A Pantheon Manifest: Exploring Important Theyyam Forms

The Theyyam tradition boasts an astonishingly vast pantheon, with estimates ranging from over 400 to 1000 distinct Theyyam forms. This diversity reflects the myriad spiritual beliefs, historical events, and local legends of North Malabar. The deities embodied in Theyyam include fierce manifestations of Shiva and Shakti (Bhagavathi), benevolent forms of Vishnu, ancestral spirits, local heroes, and even figures associated with disease prevention or social justice. Each form possesses its unique iconography, Thottam Pattukal, rituals, and social significance.1

The sheer diversity of Theyyam forms, each with its unique legend and purpose, reflects the multifaceted concerns and aspirations of the North Malabar communities, from agrarian prosperity and protection from disease to social justice and ancestral reverence. The existence of Theyyams dedicated to specific concerns (e.g., Kandakarnan for disease, Muchilot for prosperity, Pottan for equality) indicates that the spiritual landscape of North Malabar is highly localized and responsive to the immediate needs and challenges of its people. It is not a monolithic religious system but a vibrant, living tradition that addresses the full spectrum of human experience—fear, hope, injustice, well-being. Each Theyyam acts as a specific spiritual solution or commentary for a particular community need. The Theyyam pantheon thus serves as a rich ethnographic map of North Malabar's cultural, social, and spiritual concerns, demonstrating how a ritual art form can embody and address the diverse realities of its communities.

7.1. Profiling Prominent Theyyam Deities

- Bhairavan Theyyam: A fierce guardian manifestation of Lord Shiva, Bhairavan Theyyam embodies divine wrath, protection, and ritual authority. The performance reflects ancient Shaiva traditions of North Malabar, where the deity is invoked to ward off evil and uphold cosmic order. Its rituals often highlight the interplay of power, penance, and sacred fury.

- Muchilottu Bhagavathy Theyyam: A powerful mother goddess Theyyam, revered for wisdom, prosperity, and protection. Her legend often involves her emergence from fire and her association with the Brahmin community, despite being performed by historically marginalized castes. Her performances are known for their grandeur and elaborate nature.

- Pottan Theyyam: A deeply philosophical and socially conscious Theyyam, often depicted with a burning torch. Its legend recounts a debate between Lord Shiva (disguised as a low-caste individual) and Shankaracharya, challenging the rigidity of the caste system and advocating for human equality. It stands as a powerful symbol of social justice.2

- Muthappan Theyyam: One of the most popular and widely revered Theyyams, performed daily at Parassinikkadavu. Muthappan is seen as a protector deity, a giver of boons, and a compassionate listener to the woes of devotees. He is unique for his direct interaction with devotees, offering blessings and even consuming offerings like fish and toddy.3

- Gulikan Theyyam: A fierce and powerful form associated with Lord Shiva, often depicted with a dark, menacing appearance. Gulikan is believed to be a companion of Shiva and is invoked for protection from evil and negative forces.

- Kandakarnan Theyyam: A Theyyam invoked to ward off diseases and epidemics, particularly smallpox. Its performance is believed to cleanse the community and protect its members from illness.

- Kadavankottu Makkam Theyyam: Kadavankottu Makkam or Kadangot Makkam Theyyam is, known for its elaborate costumes, dynamic dance, and powerful music. The performance enacts the tragic legend of Makkam, a noblewoman falsely accused by her brothers' wives of an affair, leading to her and her children's murder; she was later elevated to divine status and worshipped as a goddess.

- Vishnu Murthy Theyyam: A fierce Vaishnava Theyyam, often associated with the legend of Narasimha (Vishnu's man-lion avatar). It is invoked for protection and justice, and its performance is characterized by intense energy and dramatic movements.

- Kandanar Kelan Theyyam: A powerful Theyyam symbolizing divine retribution and the spirit of a hunter who was burnt in the forest. Performed in Kannur and nearby regions, it reflects themes of courage, vengeance, and justice, accompanied by fiery rituals and intense rhythmic movements.

- Pulimaranja Thondachan Theyyam: Pulimaranja Thondachan is revered as a powerful ancestral guardian rooted in the agrarian and forest-based traditions of North Malabar. This Theyyam represents a lineage protector who embodies courage, territorial authority, and the primal energy associated with woodland spirits. The performance emphasizes the deity’s role in safeguarding communities, mediating disputes, and ensuring prosperity through ritual power and clan memory.

- Kuttichathan (Shasthappan) Theyyam: Kuttichathan, also known as Shasthappan, is one of the most dynamic and popular deities in the Theyyam tradition, revered for his protective, corrective, and justice-oriented nature. This Theyyam embodies a youthful yet fierce divine presence who confronts evil, safeguards households, and restores moral order through ritual authority. The performance highlights the deity’s association with fairness, spiritual discipline, and the power to aid devotees facing obstacles, disputes, or hidden adversities.

The specific legends and characteristics of individual Theyyam forms, such as Pottan Theyyam's social commentary or Muthappan's direct interaction, contribute significantly to the unique narrative and identity of North Malabar, distinguishing its cultural landscape from other regions of Kerala. The fact that a revered deity like Pottan Theyyam explicitly challenges caste hierarchy within the ritual space speaks volumes about the historical and ongoing social dynamics in North Malabar. Similarly, Muthappan's accessibility and direct engagement with devotees suggest a more intimate and less mediated relationship with the divine compared to more formal temple worship. These unique attributes differentiate North Malabar's spiritual ethos. They are not merely local variations but define a distinct regional identity that values direct engagement, social critique, and a more accessible form of divinity. The individual narratives and performative styles of specific Theyyam forms are crucial in shaping and articulating the unique cultural identity of North Malabar, making the region's spiritual and social landscape distinct and deeply resonant with its local traditions.

8. Theyyam and Thirayattam: A Comparative Study

Theyyam and Thirayattam are two prominent ritualistic art forms indigenous to North Malabar, Kerala. While sharing several fundamental characteristics, they also exhibit crucial differences that highlight divergent evolutionary paths within a shared cultural landscape.

8.1. Analyzing Similarities

Both Theyyam and Thirayattam are ancient, ritualistic art forms indigenous to North Malabar, Kerala. Both involve the temporary embodiment of a divine or heroic spirit by a human performer. They both rely on elaborate costumes, intricate face painting, and distinctive headgear to transform the performer into the divine manifestation. Both are hereditary traditions, with the right to perform passed down within specific communities. They are performed to appease deities, seek blessings, and maintain community well-being. Finally, both are accompanied by traditional percussion instruments, prominently including the Chenda and Elathalam.

8.2. Crucial Differences

Despite their geographical proximity and surface-level similarities, Theyyam and Thirayattam represent distinct evolutionary paths of ritual art, reflecting different historical influences and serving nuanced spiritual and social functions within North Malabar. The deeper roots of Theyyam in pre-Aryan, tribal worship suggest a more indigenous, perhaps less Sanskritized, origin, focusing on local spirits and social commentary. Thirayattam, with its stronger temple connection and broader instrumental ensemble, appears to have integrated more classical or mainstream Hindu elements. This divergence suggests that even within a shared cultural landscape, different social groups, historical periods, or spiritual needs led to the development of distinct ritual traditions, each fulfilling a specific niche and preserving unique aspects of the region's heritage. They are not merely variations but parallel, yet distinct, cultural expressions.

Furthermore, the specific differences in performing castes, primary deities, and performance venues between Theyyam and Thirayattam serve as crucial markers of distinct social and religious identities within North Malabar, reflecting the nuanced stratification and diverse spiritual allegiances of its communities. The hereditary right of specific castes (e.g., Vannan for Theyyam, Perumannan for Thirayattam) to perform certain deities in particular settings reinforces the idea that these rituals are not universally interchangeable. They are deeply tied to the identity, history, and spiritual practices of those specific communities. For example, a community that primarily patronizes a Bhadrakali kaavu and engages with Thirayattam might have a different historical or social lineage than one that primarily worships a Theyyam in a kavu associated with ancestral spirits. The ritual form thus becomes a powerful, embodied marker of a community's unique spiritual heritage and social standing within the broader regional context.

Table: Comparative Analysis: Theyyam vs. Thirayattam

| Feature | Theyyam | Thirayattam |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin/Evolution | Generally older, with pre-Aryan, tribal, and Dravidian roots, evolving from animistic and ancestral worship.4 | Often seen as having a more pronounced influence from Tantric and Vedic traditions, with a stronger connection to temple rituals and a more Sanskritized approach.5 |

| Primary Performance Venues | Primarily performed in kavus (sacred groves), ancestral homes (tharavadu), and occasionally temple courtyards. Often a community-centric event. | Almost exclusively performed within the courtyards of kaavus (temple-like sacred spaces) dedicated to specific deities, particularly Bhadrakali. |

| Key Deities Represented | Features a vast and diverse pantheon, including fierce Shiva forms, Mother Goddesses (Bhagavathi), Vishnu forms, ancestral spirits, local heroes, and figures of social commentary. | Primarily focuses on Goddess Bhadrakali and her fierce forms, along with Shiva, Vishnu, and ancestral spirits. The range of deities is generally narrower. |

| Primary Performing Castes | Performed by specific historically marginalized communities such as Vannan, Malayan, Velan, Mavilan, Pulayar, Parayan, and Nalkadaya.6 | Predominantly performed by the Perumannan community, with other specific castes also involved in certain regions. |

| Key Ritual Elements/Phases | Distinct phases like Vellattam (prelude), Thottam (chanting and invocation), and the main performance. Thottam Pattukal are central to the narrative and trance induction. | Key elements include Thira (the main performance where the deity manifests), Kolam (the elaborate costume and makeup), and Kalamezhuthu (drawing ritualistic patterns on the floor with colored powders, which is then erased by the performer). |

| Distinct Musical Instruments | Primarily uses Chenda, Elathalam, and Kuzhal. | Utilizes a broader range of percussion instruments including Chenda, Ilathalam, Kombu, Kuzhal, Thimila, and Maddalam, often resulting in a more complex orchestral accompaniment. |

| Geographical Concentration | Predominantly in the districts of Kannur and Kasaragod in North Malabar. | Found in parts of Kannur, Kozhikode, and Malappuram districts. |

9. Theyyam's Role in North Malabar Identity

Theyyam actively shapes community identity, fosters social cohesion, and perpetuates cultural values in North Malabar. It functions as a dynamic cultural anchor for North Malabar communities, providing stability and continuity in a rapidly changing world by continuously re-enacting core cultural values, historical narratives, and social dynamics.

9.1. In-depth Analysis of Theyyam's Cultural Impact

Community Identity and Cohesion: Theyyam festivals are annual or biennial events that unite entire communities, transcending social divisions. The shared experience of witnessing the divine manifestation, participating in the rituals, and receiving blessings fosters a strong sense of collective identity and belonging. The cycle of Theyyam performances often dictates the social calendar of North Malabar villages, marking seasons and reinforcing community bonds.1

Preservation of Oral History and Lore: Through Thottam Pattukal and the performance itself, Theyyam serves as a living archive of North Malabar's oral history, myths, and legends. It connects communities to their ancestral past, preserving narratives that might otherwise be lost. Children grow up immersed in these stories, ensuring intergenerational transmission of cultural knowledge.

Spiritual and Emotional Solace: For devotees, Theyyam offers a direct, unmediated interaction with the divine. The manifested deity listens to their problems, offers advice, provides solace, and grants blessings. This direct spiritual engagement provides immense emotional and psychological comfort, acting as a source of hope and resilience for individuals and communities.2

Platform for Social Commentary and Justice: As demonstrated by Pottan Theyyam, the ritual provides a unique, sanctioned space for social critique and the articulation of grievances, particularly from historically marginalized communities. The deity, through the performer, can question social injustices and advocate for equality, making Theyyam a dynamic force for social reflection and, at times, reform. Beyond its spiritual function, Theyyam serves as a unique negotiated space where traditional power dynamics are temporarily inverted, allowing marginalized communities to exercise agency and voice within a sacred context, thereby influencing social dialogue and potentially fostering incremental social change. The temporary inversion of hierarchy is not just a symbolic act; it is a performative act of empowerment. The performer, embodying the deity, gains a voice that transcends their everyday social status. They can directly address grievances, offer critiques, and even issue commands that are respected due to the divine presence. This creates a ritualistic space where social norms are suspended, allowing for a unique form of dialogue and negotiation between different social strata. While the inversion is temporary, the experience of having agency and being revered, even for a brief period, can have lasting psychological and social effects, subtly influencing social relations and fostering a sense of dignity among the performing communities.

Economic and Artistic Ecosystem: Theyyam supports a vibrant ecosystem of artisans involved in crafting the elaborate costumes, headgear, and makeup. The festivals also generate local economic activity and, increasingly, attract cultural tourists, contributing to the region's economy while raising global awareness of the art form.

9.2. Its Enduring Relevance in Contemporary North Malabar Society

Despite modernization and changing social structures, Theyyam continues to hold profound relevance. It remains a powerful symbol of cultural pride and regional distinctiveness for North Malabar. In an era of globalization and rapid social change, many traditional practices fade. Theyyam, however, persists because it is not a static relic. Its annual cycle provides a rhythmic, predictable structure to community life. Its narratives, such as those of Pottan Theyyam, allow for contemporary relevance. Its capacity for direct interaction with the divine offers personal solace that modern institutions often cannot. By embodying and re-enacting core myths and social values, it constantly reinforces a shared past and collective identity, providing a sense of rootedness and continuity amidst flux. Theyyam's ability to adapt, for example, by incorporating new deities or addressing contemporary social issues, while maintaining its core traditional elements ensures its continued resonance with new generations. Theyyam serves as a reminder of the deep spiritual connection to the land and ancestors, offering a counter-narrative to the rapid pace of modern life and global influences.

10. Conclusion: The Living Legacy of Theyyam

Theyyam, the ritual art form of North Malabar, stands as a compelling testament to the enduring power of indigenous traditions. Its ancient, syncretic origins reveal a remarkable capacity for evolution, absorbing diverse influences while maintaining its distinct identity as a living oral tradition. The profound transformative power of its rituals, where elaborate aesthetics and sacred chants culminate in divine embodiment, creates an immersive spiritual experience for both performer and devotee.

A unique aspect of Theyyam lies in its social dynamics, particularly the temporary inversion of caste hierarchies during performance. This dynamic transforms Theyyam into a powerful space for social commentary and agency, especially for historically marginalized communities. The vast and diverse pantheon of Theyyam deities, each with its unique narrative and purpose, reflects the multifaceted concerns of the North Malabar communities, from agrarian prosperity and protection from disease to social justice and ancestral reverence. Furthermore, the specific sacred venues, from ancient kavus to ancestral homes, reinforce Theyyam's deep connection to local communities and their environment.

When compared with Thirayattam, a related ritual art form, Theyyam's distinct characteristics—in terms of origin, primary deities, performing castes, and ritual elements—underscore the nuanced and rich cultural landscape of North Malabar. This comparison reveals that the region's ritual traditions are not homogenous but a mosaic of distinct expressions, each contributing to the unique identity of its communities.

Ultimately, Theyyam is a fundamental pillar of North Malabar's cultural identity. It functions as a cohesive force that binds communities, meticulously preserves historical memory, and provides profound spiritual solace. It acts as a dynamic cultural anchor, continuously re-affirming shared values and narratives, thereby ensuring continuity amidst the currents of change. Despite the challenges of modernization, Theyyam continues to thrive, adapting while maintaining its core essence. Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to connect individuals directly to the divine, offer a sanctioned platform for social expression, and provide a powerful sense of belonging. The living legacy of Theyyam is a compelling demonstration of the resilience and richness of indigenous traditions, offering valuable insights into the intricate interplay of ritual, society, and identity within a unique cultural landscape. Its continued study and appreciation are vital for understanding the depth of human cultural expression.

References

- Kurup, K.K.N. (1973). The Cult of Teyyam and the Hero-worship.

- Namboodiri, M.V. Vishnu. (1999). Theyyam: Art and Ritual.

- Nambiar, A.K. (2001). Ritual Arts of Kerala: Teyyam.

- Jayarajan, V. (2012). Teyyam: A Living Heritage.

- Varier, Raghava. (2010). Malabar Theyyam: A Theatrical Study.

- Kosambi, D. D. (1962). Myth and Reality: Studies in the Formation of Indian Culture.

- Karippath, R. C. (2019). The World of Theyyam. Kairali Books Private Limited.

- Menon, Dilip. (1993). The Moral Community of the Teyyattam- Popular Culture in Late Colonial Malabar. Studies in History, Sage Publications.

- Parassinikkadavu Sree Muthappan Temple. About the Temple. Retrieved from temple.muthappan.in.

- Kerala Tourism. Theyyam. Retrieved from keralatourism.org/kerala/theyyam.

- District Tourism Promotion Council (DTPC) Kannur. Theyyam Calendar. Retrieved from dtpckannur.com/theyyam-calendar.

- The Hindu. Theyyam, a ritual art form, to go online to keep its tradition alive. (2020, December 11). Retrieved from thehindu.com.

- D'Source. Theyyam - Kerala. Retrieved from dsource.in/resource/theyyam-kerala/theyyam.

- ResearchGate. Gods and the Oppressed: A Study on Theyyam Performers of North Malabar. Retrieved from researchgate.net.