III. The Thottam Pattu: Makkam’s Ballad as a Tool for Social Critique

A. Understanding the Role of the Thottam Pattu

The Thottam Pattu is the sacred verbal component of the Theyyam ritual. These are narrative ballads sung by the ritual performers, typically belonging to communities like the Vannan or Malayan, in the sacred space just before the main Theyyam performance commences.3

The Thottam is the orally-transmitted Ithihasam (mythology) of the deity, responsible for narrating the life, suffering, death, and divine transformation of the god or goddess. Its recitation is critical, guiding the performer into the character’s consciousness and preparing the audience for the divine entry.2

For Makkam, the Thottam Pattu is the primary vehicle through which her story of betrayal is kept alive. It functions not just as historical narrative but as a powerful, public articulation of social critique.

B. Makkam’s Ballad as a Feminist Text and Subversion of Patriarchy

Scholarly analysis consistently places Makkam Bhagavathy’s Thottam among the most significant oral texts that embody female resistance within the Theyyam tradition, often studied alongside the narratives of Muchilottu Bhagavathy and Neeliyar Bhagavathy.3

These ballads serve as socio-religious documents where the oppressed voice finds expression through sanctioned spiritual folklore.3

The Thottam Pattu concerning Kadangot Makkam provides a sanctioned public platform for articulating resentment against the patriarchal structures that led to her death. The narrative reflects the “thinking and feeling of the women’s collective”.2

Because these ideas are preserved within the ritual context, they carry an inherent virtue that allows them to openly challenge male-constructed notions of behaviour and expose the evil effects of customs on women’s lives.3

The ballad explicitly details the role of Makkam’s sisters-in-law in exploiting her ritual impurity (menstruation/Vaniyan incident).3

This detail highlights a sophisticated understanding of oppression: it is not solely the male violence that causes the tragedy, but the way women themselves are coerced or choose to participate in enforcing patriarchal norms, often driven by personal jealousy and orthodox beliefs.3

By highlighting this dynamic of double oppression, where female resentment weaponises male authority, the Thottam functions as a complex moral text, using the divine justice of Makkam’s curse as a moral warning to society.3

While the oral nature of the Thottam Pattu permits subtle regional and textual variations in emphasis—some focusing more on Makkam’s suffering, others on the ferocity of her vengeance, and still others on her role as a protective mother—the central theme of justice achieved through sacred power remains constant.3

The Kadangot Makkam Narrative Arc and Analytical Interpretation

| Narrative Stage |

Key Event |

Anthropological Significance (Resistance) |

| Early Life & Privilege |

Makkam receives education; born for Tharavad continuity (Marumakkathayam). |

Challenges conventional gender performativity; her high value as the matrilineal cornerstone made her a prime target for internal conflict.3 |

| Conflict Incitation |

Sisters-in-law exploit Makkam's ritual impurity (menstruation/Vaniyan incident). |

Direct critique of rigid customs and social traditions when they are used as tools for oppression, fuelled by female jealousy.3 |

| Martyrdom |

Makkam, children, and Mavilan are killed by her brothers. |

The ultimate act of victimhood; illustrates male authority prioritising toxic ego and "honour" over the fundamental duties of kinship and justice.3 |

| Divine Vengeance |

Makkam transforms into a deity and destroys the ancestral Tharavad via a curse. |

A spiritual strategy against oppression; the achievement of justice through sacred power that human law failed to deliver.3 |

| Institutionalisation |

Shrines established; Makkam is permanently worshipped as Makkappothi. |

Folklore and ritual serve as a permanent vehicle for female resistance; a collective acknowledgement and sanctification of the victim's innocence.3 |

IV. The Embodiment of Makkappothi: Ritual Transformation and Aesthetics

A. The Ritual Continuum: Preparations and the Divine Entry

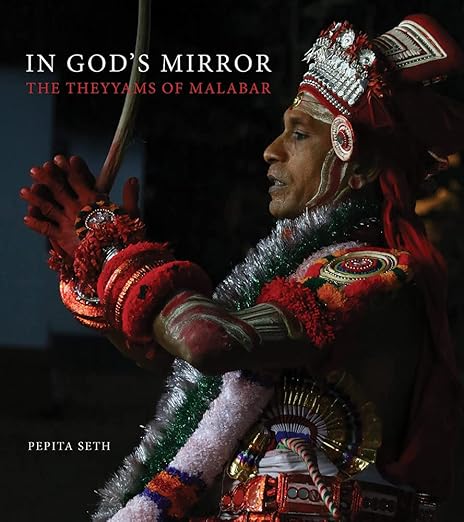

The transformation of the Theyyam performer into the deity Kadavankottu Makkam, or Makkappothi, is an arduous, multi-stage ritual designed to fully dissolve the human identity and manifest the divine.1

These ceremonial preparations are exhaustive, involving chanting and focused concentration that can take eight to ten hours before the dance commences.1

A critical component of this transition is the Mughamezhuthu, or face painting. This process involves the meticulous application of natural colors, traditionally derived from rice flour, turmeric, and charcoal.2

Given Makkam’s powerful status as an avenging goddess, the color red is predominant, mixed traditionally from turmeric and limestone, symbolizing the intense energy, power, and righteous anger required to fulfill her divine mandate.2

Although the precise Mughamezhuthu design for Makkappothi is complex and can vary slightly, as a Bhagavathy Theyyam she would typically bear intricate, fierce patterns designed to convey the magnitude of the sacred power that destroyed the Tharavad.2

This intense preparation culminates in two specific, essential actions that bridge the human and the divine realms. First, the performer consumes madhyam (toddy).1

This is not merely an act of intoxication; it is a ritualistic consumption believed to suppress the performer's personal, human consciousness, thereby creating a vacuum necessary for the deity’s arrival.1

This aligns with advanced philosophical concepts found in Hindu texts such as the Yoga Vasistha, which describe parakāya praveśanam, the entry of a divine entity into a human body.1

B. The Climax: Mudi and Parakāya Praveśanam

The final, definitive moment of transformation occurs with the placement of the Mudi (sacred headgear) upon the performer’s head.1

This action symbolizes the complete and final entry of the deity’s consciousness into the performer’s body. At this point, the human individual ceases to be, and Makkappothi the goddess stands manifest.

The visual aesthetics of Makkappothi’s Kolam (costume) are designed to reflect the fierce power she attained. As a Bhagavathy Theyyam, her costume is intricate and highly symbolic.2

It would typically include significant ornaments, such as the Mudi itself, elaborate breastplates (Marmula), decorative amulets, bangles (Katakam and Chutakam), and possibly the long silver teeth ornament known as ekir.2

These garments, often crafted from coconut fronds, areca leaves, and silver/gold adornments, visually articulate the transition from Makkam’s vulnerable mortal form to her powerful, celestial existence.

C. Anugraham (The Blessings) and Community Function

Once the deity Makkappothi is fully embodied, the ritual dance begins, accompanied by dynamic drumming. The purpose of this performance is multifaceted: to reenact the myth, to express the deity’s power, and critically, to dispense Anugraham (blessings) directly to the community.2

The Theyyam listens directly to the sorrows of the devotees, offering protection, guidance, and pronouncements of justice.2

The ritual functions of Makkappothi are deeply tied to her myth of motherhood and martyrdom. The Theyyam performance is conducted as part of the annual festivals of her specific shrines, or as a special offering sponsored by families.2

Notably, Makkam Theyyam is frequently sponsored by families who wish for children.2

This function serves as the ultimate spiritual reconciliation for Makkam, transforming her personal tragedy into a source of collective life affirmation for the devotees.

Theyyam Ritual Structure and Makkappothi’s Requirements

| Ritual Component |

Time/Duration |

Makkam Specifics & Performing Communities |

| Preparatory Narrative |

Before performance |

Recitation of the Thottam Pattu, recounting Makkam’s tragic myth and preparing the audience for the manifestation of the avenging deity.1 |

| Transformation |

8–10 hours |

Mughamezhuthu (face painting) using natural colors, with symbolic red predominating; assembly of the complex Kolam.1 |

| Divine Entry |

The climax |

Consumption of Madhyam to suppress ego; installation of the Mudi; marking the Parakāya Praveśanam of Makkam’s divine consciousness.1 |

| Performers' Origin |

Hereditary right |

Traditionally performed by specialized ritual castes, primarily the Vannan and Malayan communities.2 |

| Purpose of Offering |

Annual or Special |

Performed to secure blessings, notably for fertility (wishing for children) and familial prosperity.2 |

V. The Subaltern and the Sacred: Caste Dynamics and Makkam’s Worship

A. The Custodians of the Sacred: Vannan and Malayan Communities

A central sociological tension defines the worship of Kadavankottu Makkam: the disconnect between the deity’s high-caste, elite origin and the marginalized communities who serve as her mandatory ritual custodians. Makkam originated from the Kadangot Nambiar family, a group traditionally situated high within the social stratification of North Malabar.2

However, the act of channeling and performing the Theyyam, including Makkappothi, is the hereditary right and traditional occupation of specific communities categorized as Scheduled Castes, principally the Malayan and Vannan communities.2

This ritual hierarchy dictates that the divinity must be mediated through the traditionally marginalized. While the worshipping audience may consist of individuals from all castes, the physical manifestation of the divine power rests entirely with the Malayan or Vannan performer.2

Although the Malayan and Vannan perform the Theyyam, the Thiyyar community traditionally holds the right to cancel any Theyyam performance if necessary, indicating a complex, shared system of ritual governance beyond simple binary caste dominance.1

B. Theyyam as Counter-Hegemony: Transcending Social Status

The paradox of the high-caste goddess Makkam being embodied by the low-caste performer forms the sociological foundation for Theyyam's role as a mechanism for counter-hegemony.2

The power transfer embedded in the ritual challenges and temporarily inverts the social order.

The myth demonstrates the moral failure of the dominant social structure: Makkam’s powerful Nambiar brothers, acting under the corrupt influence of male-centric honor, murdered the cornerstone of their own Tharavad.2

Makkam’s subsequent divine vengeance explicitly condemns that dominant social authority.2

When the deity Makkam manifests through a performer from the Vannan or Malayan community, the divine power rejects its community of origin and sanctions the marginalized groups as moral custodians of justice.

The ritual space physically enacts this socio-political critique. When the Theyyam embodies the divine energy, it is venerated by people of all castes. In that sacred space, "there is no power beyond the Theyyam".2

C. Architectural Focus: The Kavu and Mundya

Following her apotheosis, Makkam specifically requested that a shrine be built in the Tharavad (ancestral home), reinforcing the intimate, localized nature of her power.2

Makkam Theyyam is performed as part of the annual festival of these shrines, often taking the form of family Kavus (sacred groves) or Mundyas.2

By demanding worship at the site of her human tragedy, Makkam transforms the physical space of her oppression into the permanent locus of her sacred authority.

VI. Makkam’s Legacy: Conclusion and Contemporary Cultural Footprint

A. The Enduring Power of Vengeance and Justice

Kadavankottu Makkam Theyyam offers far more than religious devotion; it provides a comprehensive moral framework for evaluating human behavior and social structures. Makkam’s story synthesizes the intense suffering of a human woman with the restorative power of a fierce, avenging deity.

Her life represents the ultimate resistance: a woman who achieved through sacred power the fulfillment of ambitions—the restoration of her honor and the punishment of her abusers—that were impossible within her mortal life.2

The ultimate destruction of the ancestral home by her curse serves as a moral lesson, ensuring the community recognizes the profound consequences of slander, injustice, and patriarchal violence. Furthermore, her redemption as Makkavum Makkalum transforms her martyrdom into a benevolent, life-giving force.

B. Integrating Kadavankottu Makkam Theyyam into Kerala Folklore Studies

For contemporary cultural analysts and students of Kerala folklore, Kadavankottu Makkam Theyyam serves as a vital case study in several domains:

- Feminist Critique and Resistance: Makkam’s myth exemplifies how indigenous folklore traditions articulate and preserve narratives of female resistance against patriarchy.2

- Caste Dynamics and Counter-Hegemony: The ritual mediation of Makkam’s high-caste tragedy by low-caste performers (Vannan/Malayan) offers a powerful lens on counter-hegemony.2

- Oral Tradition and Social Memory: The continued vitality of the Thottam Pattu ensures the cultural memory of Makkam's struggle and justice remains alive.2

Kadavankottu Makkam Theyyam stands not merely as a regional ritual but as a sophisticated cultural mechanism that critiques historical injustices while offering spiritual redemption and tangible blessings.

References

- K. K. N. Kurup, Aspects of Kerala History and Culture, College Book House, 1977.

books.google.com

- Vanidas Elayavoor, Lore & Legends of North Malabar, D.C. Books, 2016.

keralafolklore.com