Pottan Theyyam: The Voice of Equality and Protest in Kerala’s Ritual Landscape

Courtesy: ai Shekar Kannur, CC BY-SA 4.0 (License), via Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

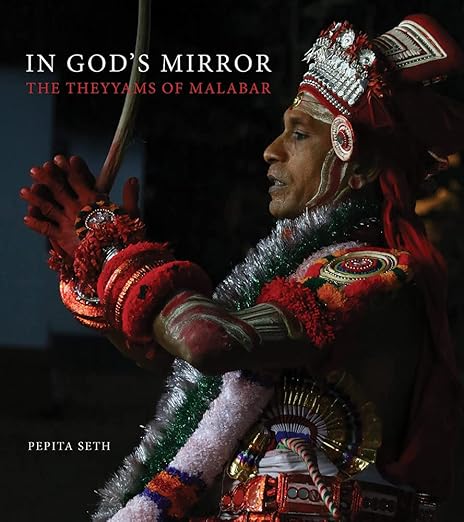

Among the many ritual performance arts of North Malabar, Kerala, Pottan Theyyam stands apart as a living allegory of protest, compassion, and spiritual knowledge. Known both as Pottan Daivam and Pottan Theyyam, this sacred performance embodies a powerful message of social equality and moral awakening. Within the broader Theyyam tradition of Kerala, Pottan Theyyam emerges not merely as a ritual spectacle but as an ethical dialogue between divinity and humanity — a dramatic confrontation with the injustices of caste and ignorance.

Performed primarily in the Kannur and Kasaragod districts, the Theyyam reveals the moral philosophy of Kerala’s folk culture, where gods walk barefoot among humans and question their actions. In the folk imagination, Pottan Daivam is often seen as a form of Lord Shiva disguised as a humble, socially ostracized man, whose words and gestures challenge the arrogance of the privileged. His laughter and anguish, performed through rhythmic body movements and fiery dialogue, become a medium of divine criticism.

In a region historically shaped by varna-based hierarchies and agrarian servitude, the Pottan Theyyam performance continues to act as a public stage of moral reflection. Scholars such as K. K. N. Kurup describe Theyyam as “a social text where the marginalized reinterpret divinity through performance”[1]. In this sense, the ritual becomes not only an act of worship but a critique of the social order itself — where divinity speaks through the oppressed.

Historical Context and Origins

The origins of Pottan Theyyam are deeply rooted in the ritual landscape of North Malabar’s folk religion, which evolved through centuries of interaction between Dravidian spirit worship and Shaiva philosophy. Folklorists like M. V. Vishnu Namboothiri note that Pottan Theyyam belongs to the oldest layer of Theyyam traditions that combined ancestral hero worship with philosophical allegory[2].

The word “Pottan” itself has been interpreted in multiple ways. In colloquial Malayalam, it refers to a ‘fool’ or ‘madman’, yet within the ritual context, the word carries a paradoxical meaning — a divine fool who reveals the truth through apparent madness. This aligns with Indian spiritual archetypes where saints and yogis appear mad to worldly eyes, as in the concept of “unmāda bhakti” or divine frenzy.

According to regional oral traditions, Pottan Daivam is associated with Sree Sankaracharya, the great Advaita philosopher from Kalady. One of the most enduring legends narrates a dialogue between Shankara and a low-caste man (Pottan), who stops the philosopher’s path, asking, “Whom do you ask to move — the body made of five elements or the soul beyond caste?” This philosophical encounter is said to have inspired the Manisha Panchakam, where Shankara admits that wisdom transcends caste boundaries[3].

Over time, this symbolic narrative transformed into ritual theatre. The Pottan Daivam became both a spiritual ideal and a representative of the socially downtrodden, worshipped in shrines such as Kattumadam, Kandoth, and Vayanatt Kulavan temples. As historian M. P. Bhaskaran Nair observes, “In Pottan Theyyam, Kerala’s folk society found a moral vocabulary to resist caste-based discrimination”[4].

The ritual thus emerged not in elite temples but in village shrines (*kavu*) maintained by communities traditionally outside the Brahmanical hierarchy. The continuity of this ritual for centuries suggests how folk spirituality became a parallel theology of resistance, distinct from Sanskritic ritualism yet rich in philosophical insight.

Legend and Symbolism

The most familiar legend associated with Pottan Theyyam begins with a Brahmin who encounters a man smeared in ashes, laughing wildly beside a cremation ground. When ordered to move aside, the man refuses, asking a question that pierces the root of social pride: “To whom do you speak — the body of flesh or the indestructible self?” Angered, the Brahmin strikes him, only to see the man transform into Lord Shiva himself. The fire that follows is not of destruction but enlightenment — a ritual representation of Jnana Agni (the fire of knowledge).

This scene, re-enacted in performance, becomes a central philosophical motif. The performer of Pottan Theyyam lies on burning embers to symbolize the trial by truth, an act of purification and transcendence. As folklorist K. V. Krishna Iyer points out, “Fire in Theyyam is not punitive but revelatory; it exposes ignorance and reclaims dignity”[5].

Every element of costume and makeup reflects this tension between pain and enlightenment. The performer’s face, painted with bold red, white, and black motifs, signifies the cosmic dualities of ignorance and wisdom. The charred ashes applied on the body evoke the cremation ground — the ultimate equalizer where social hierarchies dissolve. The body movements are rapid, circular, and trembling, imitating both divine frenzy and human suffering.

The dialogues of Pottan Theyyam, delivered in rustic Malayalam, are among the most philosophically charged in Theyyam lore. The deity challenges the onlookers to see beyond external purity and recognize the divine essence within every being. When he utters lines like “Ninte kulam ariyān njān agniyil kidakkunnu” (“I lie on fire to know your caste”), the performance becomes a theatre of ethics — a public sermon wrapped in ritual intensity.

Pottan Theyyam’s laughter, often interpreted as mockery of social hypocrisy, represents the triumph of wisdom over ignorance. This laughter echoes the words of Basavanna and Kabir, who used poetry to question religious arrogance. In Kerala’s folk imagination, it is through such laughter that divine knowledge reclaims its human face.

Ritual Performance and Aesthetics

The enactment of Pottan Theyyam is among the most emotionally charged spectacles in the ritual performance art of North Malabar. The performance usually begins after midnight and may last until dawn, filling the shrine courtyard with the rhythm of drums and the smell of burning coconut husk. The Vannan or Velan community traditionally performs this Theyyam, upholding generations of inherited knowledge about rhythm, dialogue, and costume design.

The makeup (mukhathezhuthu) follows a codified grammar where each colour bears symbolic meaning. Red represents the burning fire of truth, white the purity of realization, and black the illusion of ignorance. The performer’s face is painted in concentric lines using natural pigments from turmeric, rice paste, and laterite. The headdress (mudi) is comparatively small but expressive, covered in palm leaves painted with red and white dyes.

The chenda, veekkan chenda, and ilathalam create a rhythmic base that alternates between slow philosophical recitations and explosive movements of divine fury. According to ethnomusicologist Dr. Rajan Gurukkal, the rhythmic cycle of Pottan Theyyam mirrors the inner movement of debate and revelation — “a sonic metaphor for conflict between ignorance and enlightenment”[6].

A distinctive moment occurs when the deity lies on the burning embers. The performer’s endurance of heat, combined with chants of “Harahara Mahadeva,” turns the act into a theatre of self-sacrifice. The audience, comprising people of all castes, watches in reverent silence — an experiential reminder that purity lies in the heart, not in social rank. The ashes are later distributed as sacred prasadam, symbolizing equality through shared dust and fire.

The visual grammar of the performance transforms the shrine courtyard into a cosmic arena. The circular dance, known locally as vattakali, represents the eternal cycle of creation and dissolution. Every spin, jump, and tremor re-enacts the metaphysical tension between knowledge and illusion. Thus, aesthetics and philosophy converge, making Pottan Theyyam one of Kerala’s most profound ritual commentaries.

Offerings (Nivedyam) of Pottan Theyyam

Credit: Uajith, CC BY 3.0 (License), via Wikimedia Commons

The offerings (nivedyam) of Pottan Theyyam hold deep spiritual and social meaning within the folk traditions of North Malabar. Unlike deities of grand temples, Pottan Theyyam — who embodies the voice of the oppressed and the seeker of truth — receives simple, humble offerings prepared by the local community. Items such as tender coconut, puffed rice (malar), jaggery, and roasted rice powder (poothari) are arranged before the ritual with heartfelt reverence.

In several shrines and household performances, betel leaf and arecanut (vettila and adakka) are also included among the offerings. These are not consumed but serve as traditional symbols of respect, dialogue, and hospitality — echoing Kerala’s folk practice of extending goodwill through these sacred elements. Their inclusion reinforces Pottan Theyyam’s connection with the everyday lives of people, where ritual and social expression merge.

Together, these offerings reflect the essence of ritual equality and community participation. Pottan Theyyam’s nivedyam is not about material luxury but about sincerity and shared emotion — embodying the belief that divine grace responds to truth and humility rather than status or wealth.

Social and Philosophical Dimensions

Beyond its visual grandeur, Pottan Theyyam functions as a vernacular sermon on human dignity. In the village imagination, the deity’s questions to the Brahmin represent a timeless inquiry into the ethics of caste and compassion. Folklorist Dr. P. K. Pokker describes it as “Kerala’s earliest democratic dialogue enacted through ritual”[7].

During the performance, Pottan addresses the gathered crowd directly, questioning their deeds, pride, and neglect of moral duties. These spoken lines, or vaakku, differ slightly from village to village but retain the central theme: the rejection of false superiority. When the deity proclaims, “Man is ashes before wisdom,” the audience experiences a collective moral introspection.

The ritual’s spatial arrangement also carries social meaning. The performer begins outside the inner sanctum, symbolizing exclusion, and later enters the shrine after proving divine identity through fire — a dramatization of social integration. This reversal of sacred boundaries parallels the historical struggles of marginalized communities to claim ritual visibility. Anthropologist Roland Hardenberg notes that such folk rituals in South India often serve as “cosmological protests” against hierarchical closure[8].

Philosophically, Pottan Theyyam embodies the Advaita idea that all beings share the same divine essence. Yet, unlike abstract metaphysics, this realization is dramatized through bodily suffering, rhythmic exhaustion, and the public display of humility. The fire bed and the ash-smeared body translate metaphysical truth into sensory experience — turning philosophy into participatory art.

Modern observers often interpret Pottan Theyyam as a folk articulation of Kerala’s long social reform movement. Before the rise of Sree Narayana Guru and Ayyankali, such rituals had already begun questioning caste prejudice through performance. In this sense, the Theyyam anticipated the language of social equality that would later shape Kerala’s modern identity.

Comparative and Cultural Analysis

Comparatively, Pottan Theyyam shares thematic affinities with other folk-religious protest traditions of India. In Karnataka, the Basava Purana narratives express similar defiance against ritual orthodoxy, while in North India, the poems of Kabir ridicule caste distinctions. Both traditions, like Pottan Theyyam, reinterpret divine truth as a social equalizer rather than a privilege of birth. Scholar David Shulman observes that “South Indian folk religion often encodes radical humanism through mythic disguise”[9].

Within Kerala’s ritual spectrum, Pottan Theyyam stands alongside Muchilottu Bhagavati and Vayanatt Kulavan as embodiments of resistance, yet its focus on philosophical dialogue makes it distinctive. While other Theyyams celebrate heroic vengeance or fertility, Pottan speaks of knowledge, equality, and ethical courage. This intellectual dimension has made it a subject of study for universities and cultural academies, including the Kerala Folklore Academy.

In contemporary Kerala, Pottan Theyyam continues to inspire art films, documentaries, and academic theses. Photographers capture its haunting imagery — the ash-covered body illuminated by flame — as a visual metaphor for enlightenment through suffering. Yet, despite this modern gaze, in rural shrines of Kandoth or Kolath Nadu, the ritual still unfolds with unbroken sincerity. The villagers gather not for spectacle but for counsel, believing that the god who once challenged the philosopher still questions their conscience each year.

The relevance of Pottan Theyyam in modern Kerala lies in its reminder that spirituality and equality are inseparable. In an age of globalization, when ritual art often risks commodification, the Theyyam continues to anchor a local moral universe. As V. V. Haridas aptly notes, “Every flame in Pottan’s fire is a syllable of Kerala’s conscience”[10].

Modern Relevance and Cultural Continuity

In contemporary Kerala, Pottan Theyyam remains both a living ritual and a subject of scholarly interest. The performance continues at village kavus and household shrines across Kannur, Kasaragod, and parts of northern Malabar, drawing villagers who seek moral counsel as much as divine blessing. Recent cultural documentation — academic theses, short films, and photographic essays — has placed Pottan Theyyam within conversations about cultural preservation and responsible cultural tourism, emphasizing the need to protect the ritual’s integrity while allowing respectful public access. These discussions often use the long-tail phrase “Pottan Theyyam ritual in North Malabar: field studies and ethical documentation” when indexing research repositories and archives.

The ritual’s endurance is also linked to its adaptability. In some communities, younger performers trained in classical theatre refine dialogue delivery to make the philosophical content more accessible to modern audiences. Meanwhile, local cultural organisations have begun archiving oral scripts and recording variant versions of the deity’s admonitions — preserving the vaakku (spoken words) that carry the ritual’s ethical core. As a result, Pottan Theyyam plays an active role in contemporary debates about ritual democratization and the politics of memory in Kerala’s cultural landscape.

However, the increased public interest brings tensions. When festival organisers stage Theyyam for tourists without appropriate community involvement, the ethical texture of the ritual risks dilution. Cultural scholars therefore urge a balanced approach: document and share Pottan Theyyam widely using the keywords that help searchers discover the ritual (for example, Kerala ritual performance art and caste protest folklore) while ensuring that communities retain authority over performance practice and ritual meaning.

Conclusion

Pottan Theyyam is more than an arresting image of ash-smeared skin and fire-lit eyes. It is a ritualized philosophy — a public theatre that questions hierarchy, exhorts ethical living, and transforms metaphysical doctrine into a communal experience. Whether seen in the small shrine courtyards of Kannur or in the pages of an academic journal, Pottan Theyyam speaks persistently about the human condition: that dignity, not birth, is the ground of the sacred.

For researchers, cultural tourists, and the curious reader, Pottan Theyyam offers a rare convergence of performance aesthetics, social protest, and spiritual inquiry. Documented responsibly, studied respectfully, and performed with community consent, it will remain a potent voice of Kerala’s ritual conscience for generations to come.

Practical Notes & Media Suggestions

- Suggested hero image alt text: “Pottan Theyyam performance in Kannur shrine, ash-smeared performer on ember bed”.

- Image captions: Always include location (village name), performer’s community (if permission given), and date of photograph to maintain ethical documentation standards.

- SEO tip: use internal links such as

/theyyam-of-keralaand long-tail anchor text like “Pottan Theyyam social equality legend and ritual study” to strengthen topical authority.

References

- K. K. N. Kurup, The Cult of Theyyam and Hero Worship in Kerala. Calicut University Publications, 1986.

- M. V. Vishnu Namboothiri, Theyyam: Ritual, Identity and Performance. Kerala Folklore Academy, 2002.

- K. P. Narayana Pisharody, Kerala Charithrathil Theyyam. DC Books, 1998.

- M. P. Bhaskaran Nair, Kerala Folklore: History and Meaning. State Institute of Languages, 2008.

- K. V. Krishna Iyer, The Cultural Heritage of Kerala. University of Kerala Press, 1973.

- Rajan Gurukkal, “Ritual Soundscapes of Malabar,” Indian Folklore Research Journal, Vol. 12, 2008.

- P. K. Pokker, “Folklore and Social Protest in Kerala,” Calicut University Journal of Humanities, 1995.

- Roland Hardenberg, The Practice of the Sacred in South India. Routledge, 2018.

- David Shulman, More Than Real: A History of the Imagination in South India. Harvard University Press, 2012.

- V. V. Haridas, “Fire and Faith: Ritual Consciousness in Malabar Folk Culture,” Journal of South Asian Studies, Vol. 27, 2020.