The Apotheosis of a Warrior: A Social Scientific Analysis of Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam

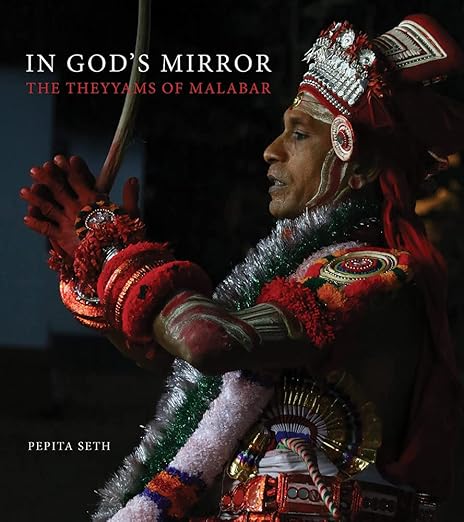

Credit: Shagil Kannur, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

1. Introduction: Setting the Context of Theyyam and Kathivanur Veeran

Theyyam, a revered ritualistic performance art form originating from the North Malabar region of Kerala, India, holds a profound place in the cultural and spiritual landscape of the area. It is more than a mere spectacle; it functions as a deep-rooted form of worship, believed to invoke and propitiate divine presence through a synthesis of dance, music, and dramatic storytelling.1 This ancient tradition, also known as Kaliyattam, has roots extending back centuries, possibly to tribal rituals and folklore, and is integral to the region's cultural identity.2

Among the myriad forms of Theyyam, Kathivanur Veeran stands out as particularly popular and widely performed in the present-day Kannur and Kasaragod districts.3 This specific Theyyam embodies the apotheosis, or deification, of Mandappan Chekavar, a Thiyya warrior whose life and transformation into a deity remain a living part of the folklore in the Kolathunadu region.2 The term 'Veeran' itself translates to 'Hero' in Malayalam, underscoring the central theme of valor and sacrifice within this narrative.4

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam. Beyond a descriptive account, this study employs established social scientific methodologies to deconstruct its foundational myth, ritualistic practices, and multifaceted socio-cultural functions. The analysis draws upon theoretical frameworks including Structuralism, particularly the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, to uncover underlying narrative patterns; Symbolic Anthropology, with insights from Clifford Geertz and Victor Turner, to interpret the meaning and social impact of its symbols and rituals; Functionalism, to examine its role in maintaining social cohesion; and theories of ritual as resistance, to understand its significance for historically marginalized communities.

Theyyam, as a cultural expression, exists in a dynamic interplay between artistic form and sacred function. It is consistently described as both a "ritualistic performance art form" and a "form of worship."1 This inherent duality means that any comprehensive analysis must consider the aesthetic dimensions of its performance—the intricate dance movements, the rhythmic music, and the elaborate costumes—alongside their deeper ritualistic purpose. The intentionality behind its execution is not solely to entertain or to tell a story, but to invoke the divine, seek blessings, and often to serve as a form of social commentary. This integrated nature of art and ritual is fundamental to understanding Theyyam's cultural positioning and its profound impact on the community.

2. The Legend of Mandappan Chekavar: Narrative and Transformation

Credit: Jinoy Tom Jacob, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The legend of Kathivanur Veeran centers on Mangatt Mandappan, a figure whose life story is deeply woven into the folklore of North Malabar. Born to Kumarappan, a prominent Thiyya landlord from Mangad Methaliyillam, and Chaki Amma of Parakayillam, Mandappan was believed to have been blessed by the goddess Chuzali.4 From an early age, he displayed a strong inclination towards martial arts, aspiring to become a warrior, a path that diverged from his father's expectations of a more conventional livelihood. Instead of engaging in work, Mandappan spent his time hunting deer and quail with friends.4 This idleness led to conflict with his father, Kumarappan, who, in a fit of rage, broke Mandappan's bow, a symbolic act of disinheritance and disapproval. Despite this, his mother, Chaki Amma, secretly provided him with rice and milk, demonstrating an enduring maternal affection.4

Saddened and angered by his father's actions, Mandappan decided to leave home. He joined friends on a business trip to the Kodagu hills, but was betrayed; his companions intoxicated him and abandoned him.4 After recovering, Mandappan wandered alone until he found refuge at his uncle's house in Kathivanoor. Here, he began a new chapter, eventually inheriting half of his uncle's property and, on his aunt's advice, establishing a successful oil business.4 During this period of newfound stability, he met and married Velarkot Chemmarathi.4 Their relationship, though marked by love, was also characterized by frequent quarrels, particularly over Mandappan's late returns home. On what would be his final day, a significant quarrel with Chemmarathi culminated in her cursing him for his tardiness.4

Shortly after this domestic dispute, news arrived that an army from Kodagu was attacking his village. Mandappan, despite the recent quarrel and his wife's curse, armed himself, saluted the deities, and went to war.4 He emerged victorious from the fierce battle. However, on his way back, he realized he had lost his pedestal ring and little finger. Disregarding his friends' warnings against returning to the battlefield alone, Mandappan went back to retrieve his lost items. It was then that the defeated Kodagu fighters, seizing the opportunity, deceitfully killed him. His body was tragically cut into sixty-four pieces.4

Chemmarathi, awaiting Mandappan's return, experienced a premonition of his death when his pedestal ring and little finger fell onto a banana leaf.4 Overwhelmed by despair, she committed suicide by leaping into Mandappan's funeral pyre.4 In the aftermath, Mandappan's uncle and son, Annukkan, upon returning from the funeral, witnessed Mandappan and Chemmarathi transformed into gods. This divine manifestation led to the first performance of Mandappan Chekavar's Theyyam, named Kathivanoor Veeran by his uncle.4

Mandappan's narrative aligns with elements of a hero's journey, encompassing departure from his initial home due to conflict, a period of initiation and new beginnings in Kathivanoor, and an ultimate, albeit tragic, return. However, the story also contains notable deviations from a purely triumphant heroic archetype. His "fatal flaw"—the decision to return to the battlefield for a lost personal item despite warnings—and his wife's curse before his departure introduce a layer of human fallibility. This nuanced portrayal suggests that his deification is not solely a recognition of his martial prowess, but also an acknowledgment of his human imperfections and the profound impact of his tragic end, critically intertwined with his wife's ultimate sacrifice. This complexity makes the deity more relatable, reflecting the intricacies of human experience and the consequences of actions, even for a revered figure. The elevation of Chemmarathi's role, through her premonition and self-immolation, is crucial; her sacrifice is not merely a footnote but an integral part of Mandappan's divine transformation.

Furthermore, Mandappan's story carries subtle socio-economic undercurrents. Born into a "huge Thiyya landlord" family, his initial preference for hunting over conventional work highlights potential tensions between traditional aristocratic leisure and emerging societal expectations for productive labor.4 His later success as an "oil merchant" suggests a shift in societal values, where economic enterprise gains prominence. The detail of his marriage to a woman, Chemmarathi, also points to the social dynamics and stratifications prevalent during that period, particularly within the Thiyya community, who were historically warriors but also occupied a specific position within the caste hierarchy.5 The deification of Mandappan, a Thiyya warrior who navigated these social and economic shifts and even transcended caste boundaries through his marriage, could be interpreted as a means to legitimize or reconcile these evolving societal realities within a sacred framework, or perhaps to elevate the status of a community hero who challenged certain social norms.

3. The Ritual Performance: Embodiment and Expression

The Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam performance is a deeply immersive and physically demanding ritual, typically staged at night or in the very early morning.4 These performances occur in open-air settings, often in "kaavus" (sacred groves) or temple courtyards, eschewing conventional stages or curtains.2 The absence of a formal stage fosters an intimate connection between the performer, the community, and the sacred space, blurring the lines between audience and ritual participant.

Before embodying the deity, the Theyyam artist, known as a Kolam, undergoes an intensive period of purification and rigorous preparation, spanning weeks. This includes fasting, meditation, and adherence to specific dietary restrictions.1 This preparatory phase is not merely physical; it is a spiritual discipline aimed at transforming the artist into a conduit for the divine spirit, preparing them for the profound shift of consciousness that occurs during the performance.

The costumes and makeup are central to the Theyyam's transformative power. Theyyam attire is elaborate, featuring intricate headgear (Mudi), heavy ornaments, and detailed face paintings crafted from natural pigments.1 Red is a dominant color in Theyyam makeup, often derived from a mixture of turmeric and limestone, symbolizing energy, power, and intensity.6 For Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam specifically, the performer wears a skirt made of bamboo pieces wrapped in red cloth.6 The face art, known as "Nakam Thazhthi Ezhuthu," distinctly features beards and mustaches, visually imbuing the performer with the deity's heroic and masculine attributes.4 The Mudi, or headgear, is a crucial element, meticulously crafted from bamboo slices, wooden planks, and natural materials like flowers, peacock feathers, and coconut leaves.2 Its placement on the performer's head is a climactic moment, believed to signify the direct entry of the deity into the artist's body, completing the metamorphosis from human to divine.3

The performance is accompanied by traditional music and dynamic dance. Percussion instruments such as the chenda, ilathalam, veekkuchenda, drum, kuzhal, perumbara, conch, cherututi, and utukku provide the rhythmic backbone, with specific rhythms varying depending on the Theyyam being performed.2 The performance typically begins with "Thottam Pattukal" (invocatory songs), recited by the dancer and drummers. These songs narrate the mythological origins and deeds of the deity, serving as oral histories that set the narrative context for the unfolding ritual.3 The choreography for Kathivanur Veeran is characterized by dynamic movement and flexibility, incorporating vigorous and energetic dance movements, including elements of Kalaripayattu (Kerala's martial art), acrobatics, sword fights, and Urumi (flexible sword) fights.4 These dance steps are structured into specific patterns known as Kalaasams.3

Symbolic spaces and elements are integral to the Kathivanur Veeran performance. The "Chemmarathi Thara," a specially prepared cell made of banana stems, multi-colored dyes, and sticks with fire, is a central feature.4 This structure is not merely decorative; it symbolizes Mandappan's wife, Chemmarathi, and its sixty-four cells are a stark reminder that Mandappan's body was dismembered into sixty-four pieces by his treacherous enemies.4 The presence of fire is another prominent element, with the Theyyam often performing around a stack of flames, increasing tempo, and making guttural sounds.3

The Chemmarathi Thara, with its 64 cells representing Mandappan's dismembered body, is a powerful symbolic representation of extreme violence and fragmentation within the myth.4 The integration of fire, recalling Chemmarathi's self-immolation, further underscores this.4 The intense physicality, martial movements, and acrobatic displays are not solely for aesthetic appeal; they are part of the performer's profound transformation into the deity.3 This suggests that the ritual actively re-enacts and processes the trauma of Mandappan's death and Chemmarathi's sacrifice, transforming these tragic events into a sacred narrative. The ritual thus functions as a communal mechanism for confronting and transcending collective trauma, where pain is transmuted into sacred power and reinforced communal identity.

The efficacy of the Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam ritual is deeply rooted in its multi-sensory experience. The dynamic movements, intense Kalaripayattu displays, rhythmic drumming, and the guttural sounds produced by the performer create an immersive auditory and visual environment.1 The elaborate costumes and makeup, along with the dramatic use of fire, further engage the senses.1 The performer's consumption of toddy, believed to suppress personal consciousness and allow divine manifestation, highlights the non-rational, experiential dimension of the ritual.3 This indicates that the ritual's power is not solely dependent on an intellectual understanding of the myth. Instead, it relies on a profound, immersive sensory engagement that facilitates the performer's "metamorphosis" and the audience's direct, embodied connection to the divine. This underscores the non-discursive, experiential nature of religious practice in Theyyam, where meaning is felt and enacted rather than merely articulated.

4. Social Scientific Analysis: Unpacking the Theyyam

4.1. Structural Analysis: Unpacking Binary Oppositions in the Legend (Lévi-Strauss)

Claude Lévi-Strauss's structuralist theory provides a method for analyzing myths by breaking them down into their constituent units, or "mythemes," which are bundles of relations. The theory posits that meaning is not isolated within individual elements but arises from the composition and relationships between these parts, often revealing universal patterns of human thought through binary oppositions.25 Applying this framework to the Kathivanur Veeran legend reveals several key oppositions and their mediations:

| Narrative Element | Binary Opposition 1 | Binary Opposition 2 | Mediation/Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mandappan's Youth | Idleness (Hunting) | Work (Landlord's Son) | New Work (Oil Merchant) |

| Leaving Home | Family Order | Individual Autonomy | New Family/Community |

| Marriage | Higher Caste (Thiyya) | Lower Caste (Chemmarathi) | Deified Union (Transcends Caste) |

| Battle Outcome | Victory | Personal Loss (Ring/Finger) | Tragic Death leading to Apotheosis |

| Mandappan's Fate | Human Mortality | Divine Immortality | Apotheosis as Hero-God |

| Chemmarathi's Fate | Wife's Grief/Suicide | Divine Union | Deification alongside Mandappan |

Mandappan's initial preference for hunting represents a "nature" orientation, contrasting with his father's expectation of "culture" or societal work.3 His journey and eventual establishment as an oil merchant mediates this tension, finding a new form of productive engagement within the cultural sphere.3 The conflict between his individual autonomy in leaving home and the traditional family order is resolved by his integration into a new community and family in Kathivanoor, for whom he ultimately fights.3 The most profound opposition is between human mortality and divine immortality; Mandappan's violent death and dismemberment are not an end but a catalyst for his and Chemmarathi's apotheosis, transcending the finality of death.3 His marriage to Chemmarathi, a woman from a "lower caste," also mediates social boundaries, as their deified union transcends the societal distinctions of caste.8 The myth of Kathivanur Veeran, through these binary oppositions, functions as a cultural mechanism to make sense of complex human experiences, social tensions, and the unpredictable nature of life and death. By transforming a flawed human narrative into a divine one, it provides a coherent framework for understanding and accepting societal norms, individual choices, and ultimate transcendence.

4.2. Symbolic Interpretations: Culture, Meaning, and Social Action (Geertz & Turner)

Clifford Geertz's interpretive approach to symbolic anthropology emphasizes "thick description," arguing that culture is a system of meanings embodied in symbols that provide "sources of illumination" for individuals to navigate their social world.27 In Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam, several elements function as potent symbols:

The Chemmarathi Thara, constructed from banana stems, multi-colored dyes, and fire, is more than a ritualistic platform.3 Its sixty-four cells explicitly represent Mandappan's dismembered body, directly linking the physical space of the ritual to the myth's most traumatic event.3 Named after his wife, Chemmarathi, it symbolizes her enduring presence, sacrifice, and the profound love that transcends death, transforming fragmentation into a sacred space of remembrance and union. The specific face art, Nakam Thazhthi Ezhuthu, with its characteristic beards and mustaches, is not merely aesthetic; it is a visual code that transforms the performer into the deity, imbuing them with the divine persona and power of Kathivanur Veeran.3 The pervasive use of fire in the performance, including the Theyyam moving around a stack of flames, can be interpreted as a symbol of purification, destruction, transformation, and the intense, even dangerous, nature of the divine presence.3 It directly references Chemmarathi's self-immolation, making it a symbol of ultimate sacrifice and spiritual union.

Victor Turner's symbolic approach, influenced by Emile Durkheim, focuses on symbols as "operators" that initiate social action and influence social processes.27 His concepts of "liminality" and "communitas" are particularly relevant. Liminality refers to the "betwixt and between" state experienced during rituals, where individuals are temporarily suspended from their normal social roles.31 In Theyyam, the performer's rigorous preparations—fasting, meditation, and dietary restrictions—and their subsequent "metamorphosis" into the deity, often involving a trance state, exemplify this liminal phase.15 The artist is neither fully human nor fully divine, existing in an ambiguous, transformative state. This allows for the temporary suspension of ordinary social hierarchies.

During the performance, particularly in the open-air settings, a strong sense of communitas emerges among the devotees.1 This unstructured, egalitarian bond temporarily dissolves conventional social hierarchies as participants collectively engage with the divine presence.21 The shared experience of witnessing the Theyyam fosters a collective bond, reinforcing communal solidarity.

Geertz views rituals as "cultural performances" that make a society's ethos visible and tangible.27 The elaborate costumes, makeup, and fire displays of Kathivanur Veeran are not merely decorative; they are symbols that convey the community's worldview, values (such as heroism and sacrifice), and emotional states. Turner's concept of ritual as a process that transforms individuals and collectivities is evident in the performer's embodiment of the deity and the audience's shared experience, which can lead to catharsis and psychological healing.21 Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam thus functions as a dynamic arena where cultural meanings are not just expressed but actively constructed and experienced. The ritual's symbolic elements and performative structure work in concert to create a profound transformative experience, both for the individual performer and the collective audience, reinforcing shared beliefs and social cohesion.

---4.3. Functionalist Perspectives: Social Cohesion and Community Role

From a functionalist perspective, social institutions and rituals contribute to the maintenance of social order and solidarity, as articulated by thinkers like Emile Durkheim.35 Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam serves several crucial functions within the North Malabar community:

Firstly, it significantly fosters **community identity and unity**. Theyyam performances are communal gatherings where villagers come together, reinforcing collective beliefs and traditions.1 This shared participation strengthens social bonds and a sense of belonging. Secondly, the myth of Mandappan, a flawed hero who achieves divinity, provides a narrative for **moral regulation and socialization**.8 His story, including his pride and its consequences, and his ultimate sacrifice, offers lessons on human behavior and the rewards of valor. The Theyyam performer, embodying the deity, also provides advice and blessings to devotees, acting as a direct moral guide.3

Thirdly, Theyyam directly addresses community needs. Women in North Malabar, for instance, worship Kathivanur Veeran specifically for a "healthy husband."3 This demonstrates a practical, functional role in addressing contemporary concerns related to well-being and prosperity, making the ritual immediately relevant to daily life. Finally, Theyyam acts as a **custodian and preserver of tradition**.7 It maintains a living connection with the past, ensuring the transmission of ancient customs, folklore, and cultural heritage across generations.

The ritual functions as a mechanism for **social reproduction and adaptation**. Functionalism suggests that rituals serve to reproduce social structures and values.35 Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam, by re-enacting the legend of a local hero and deifying him, reinforces community values such as bravery, sacrifice, and the importance of family and collective well-being. The fact that women worship him for "healthy husbands" demonstrates how the ritual adapts to and addresses contemporary social needs and anxieties, ensuring its continued relevance and function within the social fabric.3 The Theyyam is not a static tradition but a dynamic social institution that actively contributes to the stability and continuity of the community by transmitting shared values, providing emotional and spiritual support, and adapting to evolving societal concerns.

---4.4. Theyyam as Resistance and Catharsis: Addressing Historical Trauma

Theyyam holds a unique position as a **subaltern art form**, primarily performed by individuals from historically marginalized lower-caste communities, including Mannan, Velan, Malayan, and Thiyya groups.2 This grants the performers an important and revered status within the ritual, a significant departure from conventional social hierarchies.

A key aspect of Theyyam is its facilitation of a temporary **inversion of hierarchy**. Unlike the rigid Brahminical temple systems that often reinforce caste distinctions, Theyyam allows divine agency to be temporarily embodied by lower-caste individuals.21 During the performance, the performer, usually from an oppressed community, receives reverence from all present, including those from traditionally upper castes.21 This momentary subversion of rigid social structures offers a powerful, albeit temporary, reordering of social power.

Theyyam also functions as a profound medium for the expression and processing of **collective trauma**, providing a cathartic and therapeutic experience for marginalized communities.21 The intense physicality, rhythmic drumming, and fire-walking rituals offer a somatic experience that aids in trauma processing, allowing the community to physically engage with and release historical burdens.21

The myths underlying many Theyyam performances, including Kathivanur Veeran, often serve as **resistance narratives**. They recount stories of lower-class individuals who suffered under the cruelties of upper-caste society and were subsequently deified.37 The **"Thottam Pattukal"** (invocatory songs) that precede the main performance specifically highlight themes of oppression and resistance, functioning as oral histories that preserve the struggles and resilience of marginalized communities.21

Structural violence, a concept defined by Johan Galtung, is embedded within the historical caste system of Kerala, which institutionalized systemic violence against lower castes through untouchability, forced labor, and social exclusion.21 Theyyam disrupts this oppressive structure by providing an alternative space where marginalized voices are not only heard but embody divine authority.

The fact that lower-caste performers embody deities and receive reverence directly challenges the historical Brahminical hegemony and the structural violence of the caste system.13 This is not merely symbolic; it is an active, embodied subversion where the "low" temporarily becomes "high," aligning with Victor Turner's concept of liminality.31 For Kathivanur Veeran, a Thiyya warrior, his deification and subsequent worship by a broad community further solidifies this challenge to traditional caste hierarchies.3 Theyyam thus serves as a powerful socio-political act, a form of cultural resistance that provides a platform for marginalized communities to articulate historical grievances, assert their identity, and re-imagine social power dynamics, even if temporarily.

The performance of Theyyam "reenacts past injustices" and "functions as a medium for the expression and processing of collective trauma".21 This indicates that the ritual is not just about remembering historical events but actively engaging with the emotional and psychological residue of those events across generations. The physical enactment, trance states, and communal witnessing parallel modern trauma therapies, suggesting an indigenous healing tradition.21 Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam, like other Theyyams, provides a culturally sanctioned and effective mechanism for communities to collectively confront, process, and potentially heal from historical injustices and systemic oppression. It highlights the profound therapeutic potential of ritual in fostering resilience and well-being at a communal level.

| Theoretical Framework | Key Concepts Applied | Application to Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam | Understandings Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structuralism (Lévi-Strauss) | Binary Oppositions, Mythemes, Mediation | Analysis of Mandappan's legend: Home/Exile, Individual/Community, Life/Death, Human/Divine, Thiyya/Kodagu. | Reveals how the myth mediates societal contradictions and makes sense of complex experiences through structured narrative. |

| Symbolic Anthropology (Geertz) | Thick Description, Symbols as Meaning-Makers, Cultural Systems | Interpretation of Chemmarathi Thara, Nakam Thazhthi Ezhuthu, Fire. | Uncovers how ritual elements embody cultural values, worldview, and emotional resonance, making abstract meanings tangible. |

| Symbolic Anthropology (Turner) | Liminality, Communitas, Ritual Process, Symbols as Operators | Performer's transformation into deity, communal bonding during performance. | Explains how the ritual temporarily suspends social norms, creates collective solidarity, and facilitates individual and collective transformation. |

| Functionalism | Social Cohesion, Moral Regulation, Community Needs, Social Reproduction | Theyyam's role in community identity, addressing needs (e.g., healthy husbands), preserving traditions. | Demonstrates how the ritual contributes to societal stability, reinforces shared values, and adapts to contemporary community requirements. |

| Ritual as Resistance | Subversion of Hierarchy, Collective Trauma, Oral Histories, Structural Violence | Lower-caste performers embodying divinity, re-enacting injustices, Thottam Pattukal as resistance narratives. | Highlights Theyyam's function as a socio-political act for marginalized communities to express grievances, assert agency, and process historical trauma. |

5. Kathivanur Veeran's Distinctiveness and Enduring Cultural Significance

Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam distinguishes itself through several unique characteristics that set it apart within the broader Theyyam tradition. Its central focus on the apotheosis of a Thiyya warrior, Mandappan Chekavar, provides a specific narrative anchor.3 The ritual incorporates the highly symbolic "Chemmarathi Thara," a structure explicitly linking to Mandappan's dismemberment and his wife's sacrifice, symbolizing both fragmentation and enduring union.3 The distinct "Nakam Thazhthi Ezhuthu" face art, featuring beards and mustaches, is a recognizable visual marker of this particular deity.3 Furthermore, the performance is renowned for its dynamic martial movements, including Kalaripayattu displays, acrobatics, and significant fire play, adding a unique intensity to the ritual.3

The contemporary relevance of Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam extends beyond its traditional ritualistic functions. It continues to play a vital role in cultural preservation, with annual performances ensuring the continuity of ancient traditions and the rich cultural heritage of North Malabar.1 The ritual is also a subject of considerable academic interest, evidenced by scholarly books such as Lissie Mathew's "Kathivanoor Veeran: Malakayariya Manushyan, Churamirangiya Daivam" and E. V. Sugathan's children's literature, with Mathew's work even serving as a textbook in several universities.3 This academic engagement contributes to its documentation and broader understanding.

Its presence in popular culture is growing, with a film titled "Kathivanur Veeran" currently in production, indicating its continued resonance and adaptation into new media forms.3 This adaptation suggests a cultural form capable of transcending its traditional boundaries while maintaining its core narrative. Additionally, Theyyam performances attract tourism, contributing to the art form's visibility and potentially offering economic support to the performing communities, though state support for performers is noted as an area for development.1

Despite its ancient roots and ritualistic nature, Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam is not static. Its continued performance, academic study, and adaptation into popular media demonstrate its capacity to remain relevant in a changing world.3 This indicates a flexible cultural form that can simultaneously preserve its core identity while engaging with contemporary modes of expression and dissemination. The Theyyam's ability to transcend its traditional ritualistic boundaries and enter academic and popular discourse ensures its survival and continued cultural impact, highlighting the adaptive nature of cultural heritage in the face of modernization and globalization.

6. Conclusion: Synthesis, Contemporary Relevance, and Future Inquiry

Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam is a complex cultural phenomenon that transcends simple categorization as either art or ritual. This analysis has demonstrated its multi-layered significance, encompassing a foundational myth, intricate ritualistic practices, and profound socio-political implications. Through the lens of structuralism, the legend of Mandappan Chekavar reveals how it mediates fundamental societal contradictions, transforming a tragic human story into a divine narrative that makes sense of life's complexities. Symbolic anthropology, drawing on Geertz and Turner, illuminates how the ritual's elements—from the Chemmarathi Thara to the performer's metamorphosis—are not merely symbolic representations but active operators that shape cultural meaning, induce transformative experiences, and foster collective solidarity. Functionalist perspectives highlight Theyyam's role in maintaining community cohesion, transmitting moral values, and addressing contemporary societal needs. Crucially, Theyyam functions as a powerful ritual of resistance and catharsis, providing a platform for historically marginalized communities to embody divine agency, process collective trauma, and challenge entrenched social hierarchies.

The enduring significance of Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam in North Malabar is undeniable. It remains a vital source of spiritual connection, a catalyst for community cohesion, and a potent expression of subaltern history and resilience. Its continued performance, academic study, and presence in popular culture underscore its dynamic interplay with modernity, ensuring its preservation and evolving relevance in a changing world.

Further inquiry into Kathivanur Veeran Theyyam could explore several avenues. Detailed ethnographic studies focusing on the performer's subjective experience of "metamorphosis" and its long-term psychological effects could provide invaluable insights into the embodied nature of the ritual. Longitudinal studies examining the impact of modernization, increasing tourism, and media adaptation on the ritual's authenticity, community function, and economic sustainability for performing communities would also be beneficial. A comparative analysis with other "hero Theyyams" or deified figures across Kerala could help identify broader patterns of apotheosis, social commentary, and the role of ritual in shaping regional identities. Such research would contribute to a more holistic understanding of this profound cultural heritage.

References

Academic and Social Scientific Analysis

-

Geertz, C. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic Books. (This foundational work is the source for the concept of "thick description" and the interpretive approach to symbolic anthropology).

-

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine de Gruyter. (This book introduces the key concepts of liminality and communitas, essential for the structural analysis of rituals like Theyyam).

-

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. Basic Books. (A cornerstone of structuralist theory, it provides the framework for analyzing myths through binary oppositions, as applied in the article).

-

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167-191. (The source for the concept of "structural violence," which is used to analyze the caste system's impact on marginalized communities).

Books on Theyyam and Malabar Culture

-

Kurup, K. K. N. (1986). Theyyam: A Ritual Dance of Kerala. Director of Public Relations, Government of Kerala. (A key source on the general history, rituals, and performance aspects of Theyyam).

-

Mathew, L. (2012). Kathivanoor Veeran: Malakayariya Manushyan, Churamirangiya Daivam. Kerala Bhasha Institute. (A socio-cultural study specific to the legend of Kathivanur Veeran).

-

Dasan, M. (2012). Theyyam: Critique on Patronage and Appropriation. Kannur University. (This book provides an in-depth analysis of Theyyam as a subaltern art form and its relationship with caste hierarchies and resistance).

Online Articles and Websites

-

Chandran, S. M. (2016). MYTH AS A SYMBOLIC NARRATIVE. Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL), 4(4), 486-490. Retrieved from http://www.rjelal.com/4.4b.2016/486-490%20SHILPA%20M.%20CHANDRAN.pdf

-

Rajendran, S. (2019). Discourse Analysis and Ritualistic Traditions- A Study on Theyyam Art Form of Kerala. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR), 6(6), 724-728. Retrieved from https://www.jetir.org/papers/JETIR1906F86.pdf

-

The Hindu. (2013, January 22). Theyyam: Critique on Patronage and Appropriation by Prof M Dasan. Round Table India. Retrieved from https://www.roundtableindia.co.in/theyyam-critique-on-patronage-and-appropriation-by-prof-m-dasan/

-

Travel Kannur. (n.d.). Kathivanoor Veeran or Manthappan Theyyam. Retrieved from https://travelkannur.com/theyyam-kerala/kathivanoor-veeran-theyyam/

-

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Theyyam. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theyyam